Being educated by nuns is a mix of moments which, for me, included the dangers-of-diseases-one-can-get if you sit on a boy’s lap to moments of wordless understanding.

My dominant arm was wrapped in a plaster cast at the time, protecting a pin which would later be pulled out like you might remove a rusty nail from a rotting bit of timber. We were in Civics lesson and my fellow students took advantage of our diminutive teacher who was dictating from a book. My attempts to write were extremely slow. As it was a subject no-one enjoyed, my friends and mostly not-so-friends slowed the teacher down, using me as an excuse. It wasn’t the first time I’d witnessed our class bully a nun. One, the former headteacher, occasionally taught us when the school was in need of a substitute. For generations, she was known as Mouse, something of which she was unaware, even by the time she hobbled into our classroom leaning heavily on a stick. We were given a task to do, silence being the operative word of her instructions. Silence ensued.

A girl at the front suddenly shouted out, and clambered onto her desk, pointing at the teacher’s station, ‘there’s a mouse behind the desk!’ The nun pushed back her chair and shuffled to the front of the desk. Another girl stood on her desk and called out ‘it’s in front now!’ The nun tottered around to the back, until she was ‘running’ in circles around her desk. Some of the girls began to tuck their legs up under them, until, no longer able to keep it in, the initiator collapsed on her desk in fits of laughter.

One day, while suffering another hour of dictation, this time without a plaster cast, it occurred to me that Civics was quite interesting.

Years later, I stood in a classroom in the north of England facing eager faces. I taught subjects they found interesting: Psychology and Sociology. The post-16 system included subjects which students took for the sole purpose of boosting their university applications and largely resented having to do them. At first, our school offered General Studies as an option, then it offered a range of alternatives, one of which was Citizenship, which nobody wanted to teach. I looked at the curriculum and it occurred to me that it was quite interesting, just like Civics way back in a convent school. I volunteered to lead the course. There were only four takers, but students had two weeks to change options if they wanted. By the end of the two weeks, we needed another teacher.

Part of the course required the students to study a citizenship project in depth. Out of a list of examples, they collectively agreed on Transition Towns. The concept was new to me, and something I loved about the course was that it was as much a process of discovery for me as it was for them.

Transition Towns

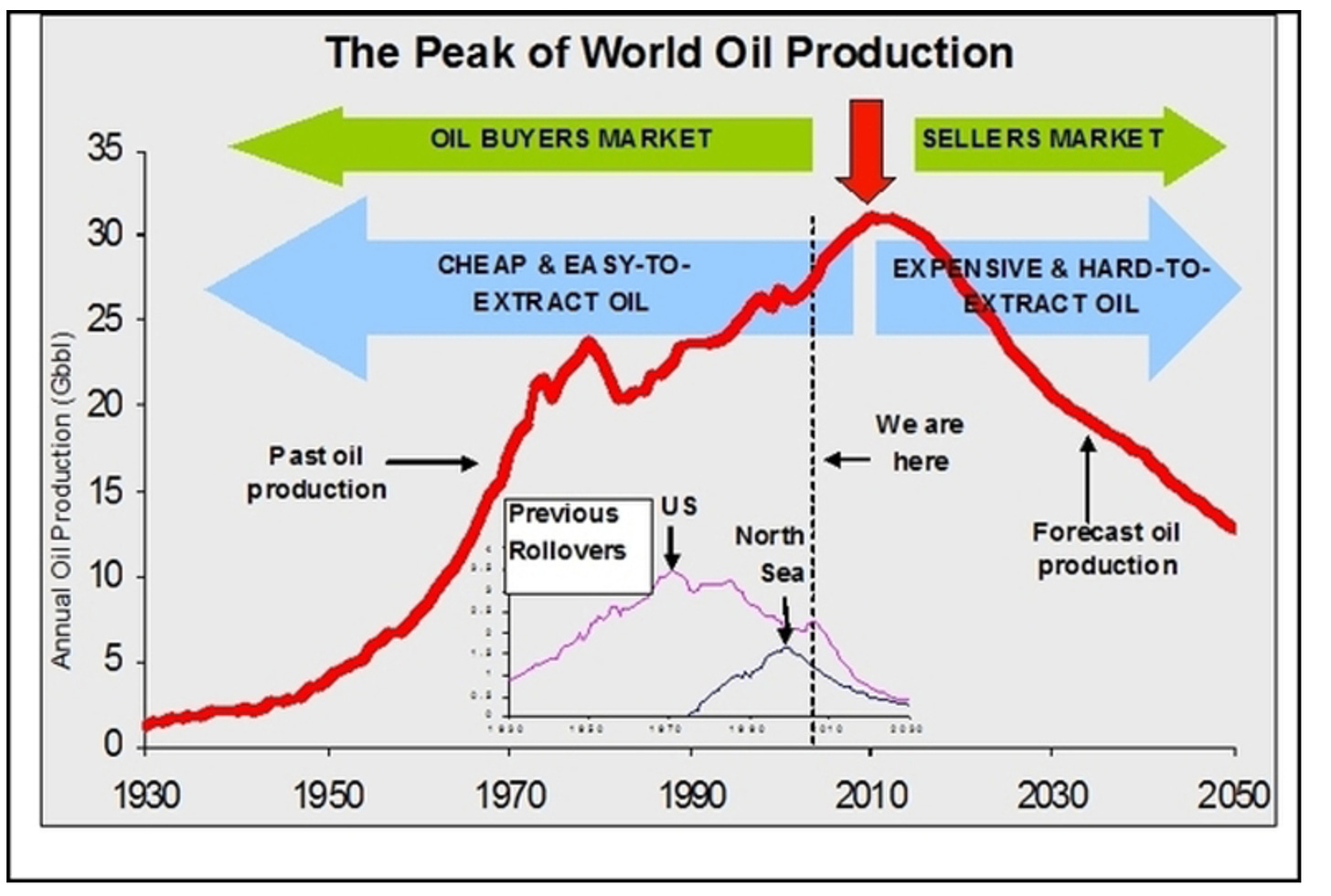

The idea for a transition town emerged in an outdoor classroom in the county of Cork, Ireland. At the time, Rob Hopkins taught about sustainable living, like natural housing, food growing and energy solutions. Rob had previously attended a lecture on ‘peak oil’. This came on the heels of a truck drivers’ protest which almost brought the UK to a halt. The country became just three days away from having no food. For Rob, this was a wake-up call to what could happen in a world without oil. In his classroom, he set his students the task of creating “an energy action plan in response to the problems posed by the advent of peak oil production”.

Peak oil is the hypothetical point in time when the quality and quantity of oil will have declined to the extent it will no longer be economically viable. Kinsale, the town in Cork, where Rob’s local solution was first proposed, took on the plan as policy. Kinsale was arguably the first Transition Town.

Back in a Yorkshire classroom, an argument ensued. First, some students studied Politics and their teacher had presented a hypothetical case against peak oil. Whether Peak Oil was a reality or not, they accepted the idea there are finite resources upon which unrealistic demands are made.

As Rob said in his 2009 TED Talk, there were four stories in response to this notion: Business as Usual, “the future will be just like the present, just more of it”; Hitting the Wall, “everything is so fragile .. it will unravel and collapse”; The Impossible Dream, “technology can solve everything”; and The Transition Response, which is the story he likes to tell.

The Transition Response

If you ask anyone involved in transition, they would describe it differently:

“I’m involved with the transition response, and this is really about looking at the challenges of peak oil and climate change square in the face, and responding with a creativity and an adaptability and an imagination that we really need. It’s something which has spread incredibly fast. And it is something which has several characteristics. It’s viral. It seems to spread under the radar very, very quickly. It’s open source. It’s something which everybody who’s involved with it develops and passes on as they work with it. It’s self-organising. There is no great central organisation that pushes this; people just pick up an idea and they run with it, and they implement it where they are. It’s solutions-focused. It’s very much looking at what people can do where they are, to respond to this. It’s sensitive to place and to scale.”

The idea is that within a given locale there are finite resources, most of which are brought in from elsewhere, from food to energy. Transition is a form of commons thinking, as described by Justin Kenrick, in collaboration with Portobello Transition town:

Commons regimes manage socio-environmental relations in ways that attend to the finite nature of human and natural systems in a way which - paradoxically - ensures their infinite abundance continues.

In contrast, dominant regimes, which operate with a policy of Enclosure, appropriate resources that were once accessible through rights and responsibilities intrinsic to being a member of a community. Enclosure is a lived reality in western societies and attempts to legally reassign lands back to the commons have not been successful.

Like Rob, Justin argues that commons thinking is:

… an important skill for rebuilding political, community and personal resilience: the ability to think in a Commons way. This way of thinking is crucial to tackling the root cause of economic and ecological meltdown, to restoring the local, national and global commons, and so recovering a future that can often - to say the least - seem precarious. Commons regimes persist and re-emerge wherever people retain the political space to concern themselves with maintaining social and ecological resilience. They persist in the face of pressure from more powerful outside forces which they seek to exploit, in a short-sighted way, the social and ecological resources upon which the community depends.

This re-emergence is evident in all of the projects we’ve discussed so far and Justin argues that Transition approaches, like the one Rob initiated, also embody commons thinking. He praises the creative and empowering approach of Transition to improve life for all. Three years after his initial TED Talk, Rob was back on stage again in Exeter. The audience was most touched when he shared the heart-felt personal responses from those who had become involved.

Back in our Yorkshire classroom, a more superficial argument arose about whether it was Kinsale, Ireland or Totnes, England that was the first Transition Town. Kinsale was the seed, but the coining of the term and its implementation first began in Totnes. Totnes was special in terms of its residents and perhaps was prime location for Transition, but not necessarily anywhere else. “It wouldn’t happen in Yorkshire,” someone drearily commented. Then came pleas for a trip down south to Totnes.

But it was happening in Yorkshire, and creeping all over the world - to more than 50 countries. I happened to have met a woman who, with her neighbours, were in the mulling stage of becoming a transition town. She agreed to deliver a talk. It wasn’t a trip to Totnes, but it broke the tedium of a normal school day.

“What do you actually do?” was the first question aimed at our visitor shortly after a video which outlined the problem more than the solution. The question made our visitor visibly relax. In their town, it was early days, but she referred to what had been achieved elsewhere. She also told them about two groups with specific goals that interested them: a clothes swap shop and a community orchard.

What did they do elsewhere?

Some of the things that emerge from it [a Transition approach] are local food projects, like community-supported agriculture schemes, urban food production, creating local food directories, and so on. A lot of places now are starting to set up their own energy companies, community-owned energy companies where the community can invest money into itself, to start putting in place the kind of renewable energy infrastructure that we need. A lot of places are working with their local schools. Newent in the Forest of Dean [England]: big polytunnel they built for the school; the kids are learning how to grow food. Promoting recycling, things like garden-share, that matches up people who don’t have a garden who would like to grow food, with people who have gardens they aren’t using anymore. Planting productive trees throughout urban spaces. And starting to play around with the idea of alternative currencies.

Transition is motivated by a desire to do something, whether it is to better know your neighbours or to tackle climate crisis. It begins by building ‘Healthy Groups’.

“When we get together, it’s like everyone is feeding everyone else. There’s this atmosphere of ‘I tell you… you tell me’. Everyone listens, then someone comes up with another idea. It’s like collective excitement, collective inspiration, collective knowledge, coming together for the profit of the group. You can feel the thrill.”

Creating healthy or constructive group settings is a skill a lot of us don’t have, and the Transition Network, a support group which emerged out of the original Transition Town, provides resources for co-creating healthy group culture. Food, it recommends, is a good place to start. Most Transition Towns begin with an individual who reaches out to their neighbours. A first action could be as simple as reducing their personal household energy bills. It could be a specific association: the nearest organisation using a Transition approach to me is one centred on art for change. In a transition approach, no-one has power, no-one leads, and the arrangement for who does what comes out of a culture of healthy group meetings. It’s a form of participatory democracy focused on community action, or do-ocracy, as Rob named it - a do-ocracy with highly positive results and outcomes for those involved.

A couple of years after the first cohort of citizens, I received an email from a former student. She was excited about working in a Transition Town and had just joined a working group. She had expected to feel isolated, away from family and friends, away from the town she’d lived in all her life. Her first experience of the working group instilled a feeling of belonging and she was hopeful about her future.

And, Justin argues, it is rational to be hopeful. Commons resources are, it is assumed, abundantly available. That abundance is ensured by the principle of my well-being being dependent on your well-being (including non-human beings). As in the Transition approach, commons thinking solves problems by working to restore relationships of trust, rather than the imposition of solutions on others.

There is a lot of trust to be restored, but there has already been a great deal of groundwork laid for a hopeful future.

Up Next

In Transition approaches local business, resources and relationships are prioritised and local currencies have been adopted to encourage local economies. Next week, we’ll take a peak at the adoption of local economies and currencies, and see how that worked out.

Embers

Although I provided a link (above) to Antonia’s post on the Doctrine of Discovery, I wanted to flag it up here. In it, she charts the history of the exploitative shift from commons to dominant regimes (Enclosure). She explores the papal bulls and the legal precedents created to support them.

I may have once provided a link to John Lovie’s series on Enclosure, a story told from a more personal perspective, but it deserves another mention in this context.

In response to last week’s post,

shared her related experience.Finally, your postcards are popping up like an early spring flourish of blooms. The experience is more than I have words for or could have hoped for. To celebrate this, I have set up a gallery page of participants, so that when you click on a participant you will be brought to their personal postcards page which will display a gallery of all their postcards (presented as a link to the original Note, like Caroline’s above). Although ready to go, it is up to you if you’re happy for your images and messages to be used in this way. If you prefer, drop me an email: safar-fiertze@protonmail.com . My plan is for the galleries to sum up the year and to be published at the end of 2024.

Thanks, Safar, for this. Thanks, too, for the link and for linking Antonia's excellent piece.

It seems to be a good day for this topic. @jill just linked to a piece from @hadden turner (I know these tags don't work in comments, but you can look them up!) https://overthefield.substack.com/p/where-you-are-is-where-you-are on the importance of acting locally, just in time to remind me that that's what I'm mostly doing.

When I moved to the island twelve years ago, our realtor took us to a meeting of Transition Whidbey, where she thought I might find my people. She was right. Within a few months, I was president of TW. We wound up winding up TW, not because it failed, but because it was redundant. We were already that kind of community. TW was kicking an open door.

I did find my tribe though. Wendell Berry said, "be famous within 15 miles". It seems to be happening.