This darksome burn, horseback brown, His rollback highroad roaring down, In coop and in comb the fleece of his foam Flutes and low to the lake falls home. A windpuff-bonnet of fáwn-fróth Turns and twiddles over the broth Of a pool so pitchblack, féll-frówning, It rounds and rounds Despair to drowning. Degged with dew, dappled with dew Are the groins of the braes that the brook treads through, Wiry heath packs, flitches of fern, And the beadbonny ash that sits over the burn. What would the world be, once bereft Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left, O let them be left, wildness and wet; Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet. (Gerard Manley Hopkins, Inversnaid, 1881)

This poem, written all of 142 years ago, is gut wrenching. I have never been to Inversnaid, but I wonder, now, how recognisable it is. Of how much wet and wildness is it now bereft?

The poem makes me want to cry.

My mother once told me I was unfeeling and cold-hearted. I was 12 years old, I hadn’t cried over the death of our pet dog. I thought it unfair, but I didn’t know how to tell her. It was a harsh thing to say to one’s child when she’d been taught to be seen and not heard, and chastised for emotional outbursts.

My mother may have had a point. I didn’t cry when she died either.

After leaving the world of work and material acquisition, I found myself crying a lot. It just happened not to be for people or dogs.

The 576 bus from Bradford in West Yorkshire passes first by the city hall, a remarkable feat of architecture from the late 19th Century. It has a distinctive clock tower and is flanked on all sides with statues of former monarchs. It’s situated on Centenary square, once lined with old cherry trees, the most amazing sight to behold when they blossomed in the spring.

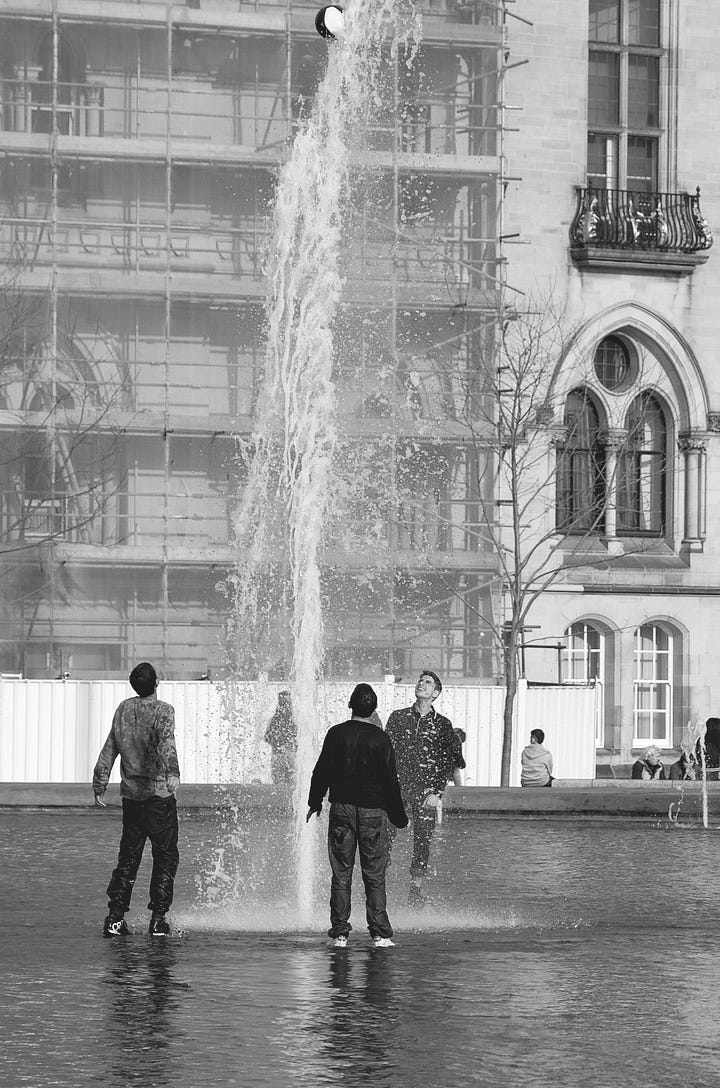

Travelling home from work on the 576 one day, I was floored by the sight of felled trees. They were not diseased. It was a move to make way for a water park.

The bus was packed. The woman sat next to me stared past, out the window at the appalling scene which had befell the city. She looked but didn’t see.

A lump formed in my throat. I tried to swallow it back. My eyes began to water. Tears turned to heaving sobs. The passengers pretended not to notice, including the woman next to me. Why didn’t they feel as enraged as I did?

A year earlier, another felled tree wreaked such strength of emotion in me that my neighbour was in danger of being punched. I was a serious karate practitioner at the time, it might have got me into a whole pile of trouble.

Our gardens were separated by a hedge. The shrub was one of those hybrid ornamentals no self-respecting bird would ever nest in. Even insects avoided it. The neighbour wanted to cut it down and replace it with a fence, to which I agreed. I could always plant something more insect and bird-friendly on my side of the fence. A couple of weeks later, the hedge was gone, a fence erected, but something else was missing - a mature hawthorn tree. It had stood just outside my living room window and blocked my nature-averse neighbours from peering in. Like the cherry trees in the city centre, it was incredibly beautiful. In Spring, it would blossom with aromatic May flowers. In winter it would don a wizened stance, stoically braving frost and snow. My fury turned to tears. I was grateful for my children’s presence, they helped dissipate the anger. But not the grief, a grief I seem to spare only for trees.

So all around him, on this earth, does every action have to lead to suffering?

Is he directly to blame for the suffering of plants and animals?

Can he not even cut down a tree without committing murder?

It’s true, when he cuts down a tree, he does kill. (from Hill by Jean Giono, 1929. Source: America Magazine.)

Death and Life are inseparable. I accept that uncompromising truth. However, what pierces my gut and wrenches out my heart is senseless, needless death. Even for people and dogs.

I used to live in a country in which had a culture of respect for fairy folk. No good would ever come of stepping into a fairy ring or chopping down the trees in which they live - hawthorns. My tree was a magical tree.

Not long after, our neighbours moved on. Nobody in the street mourned their loss, the hawthorn tree being one of many crimes. I secretly hoped for a karmic return and to ensure it didn’t land on me, the guardian of the tree, promised the universe I would plant a hawthorn tree.

That was a long time ago. Now, as steward of an acre of land, I planted hawthorns. A symbolic act. When planted, they were 15 cm high twigs. Now, they’ve put on weight and grown enough to support at least three of the fae-folk each. It will be a long time before they have the majesty of the May tree we used to love. Stewardship is an act of patience.

At about the same time I mourned lost trees, I was given a gift of a small book. It had a profound impact on me, as it has had on many readers. The story reads so much like a biography, it’s hard to believe it’s fiction.

The author, Jean Giono, was born into a humble home in Provence, France. He left school early to help support the family, but continued his love of literature, walking with a book in hand as he roamed the Provencal hills. He began to write. In his early years, his characters were peasants, and through his words he expressed an extraordinary passion for and connection with the natural world.

His simple and frugal life was halted by the First World War, in which he served at Verdun. With very few survivors from his infantry, his pacifism and anti-modernist sentiment infused subsequent work. His books revered the pastoral life, scorning the state and the political arena.

Giono’s writing has been described as a Mirror of the present.

Giono finds not indifference but a kind of reaction from the natural world, which is fully capable of rejecting the humans who live in it. Though frequently beautiful, his Provence is a denuded landscape, full of ghost villages and failed settlements, scarred by human hands but frequently without humans to fill it. Take care of the world, he warns, or it might no longer take care of you. (Robert Rubsam, 2020)

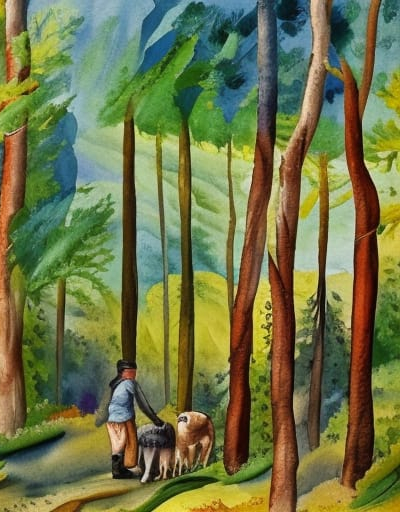

In his books, peasants are the heroes of his tale, and this is no less true in perhaps his most famous work, The Man Who Planted Trees. The simple shepherd, Elzéard Bouffier, the solitary protagonist of this short novella, emerges as the quiet hero who transforms a desolate and degraded landscape into lush green forest.

When The Man Who Planted Trees was published, readers travelled to Provence to see Bouffier’s forest for themselves. In one edition of the book, the afterword, written by Giono’s daughter, makes it clear the story is entirely fictional. Perhaps the reason it’s so easy to be convinced by the truth of the tale is in wanting so badly for it to be true. It is a story of hope so profound it drives people to the place in which the story is enacted.

While we may be disappointed to be told it is only a story, it contains an element of truth. The cast of characters may be different, and the landscape of the narrative quite unlike Provence, yet there are Elzéard Bouffiers in the world and their stories are equally remarkable.

Before I delve into these tales, this week I’d like to invite you to a (re)reading of The Man Who Planted Trees by Jean Giono, who not only inspired a generation of ecologists, but also generously gifted the novella to the world to freely distribute. It takes about half an hour to read, and in the next few posts, I will refer to aspects of the book which are pertinent today.

The copy available below was provided by the complex and sustainable urban networks (CSUN) lab at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

I also highly recommend this beautiful retelling by Frédéric Back, narrated by Christopher Plumber.

Embers

I had a good chat with

who writes . He has just begun a new series on land ownership and has taken a compelling personal angle on the issue. I am looking forward to part two!Do you know how many different varieties of potato there are? This week, I learned there are over 1,300 different varieties being grown (and saved) high in the Andes of Peru alone. Reiterating the theme of my earlier post, Gold of the Future, a BBC article expands on the importance of local seed-saving efforts globally. You can read it HERE.

Up next:

Next week’s story is that of a true life Elzéard Bouffier - the woman who planted trees.

So much to admire in this! I totally relate to a sudden grief for a cut tree. I experienced the same thing when I lived briefly in Philadephia after grad school. My living room of my 2nd-floor flat in an old rowhouse faced the street. Light was filtered by the leaves of a beautiful old sycamore that I befriended. One day, returning from work, I arrived home to find my lovely old friend reduced to a pile of sawdust. I burst into tears right there on the sidewalk. I think of that tree often.

When my son was six or seven, our neighbor across the street had to take down an old beech tree in her front yard. The parts hoisted on cables by the tree guys looked like an elephant’s foot or a giant woman’s torso. It was wrenching to lose that arching beauty. My son, who at that time loved to draw bare branching trees, made one of them into a condolence card for our neighbor.

Thank you for recommending Giono’s book. I was one of those who believed it to be true the first time I read it. I’ve had my ecological architecture students watch the film to show them they can make an impact whatever they do. I’ll try to find a before-after forest planting story from permaculture and share it with you. I can’t think of where it is at the moment.

This was excellent, Safar.

What is it about humans and trees?

Thank you so much for the mention. 🙏