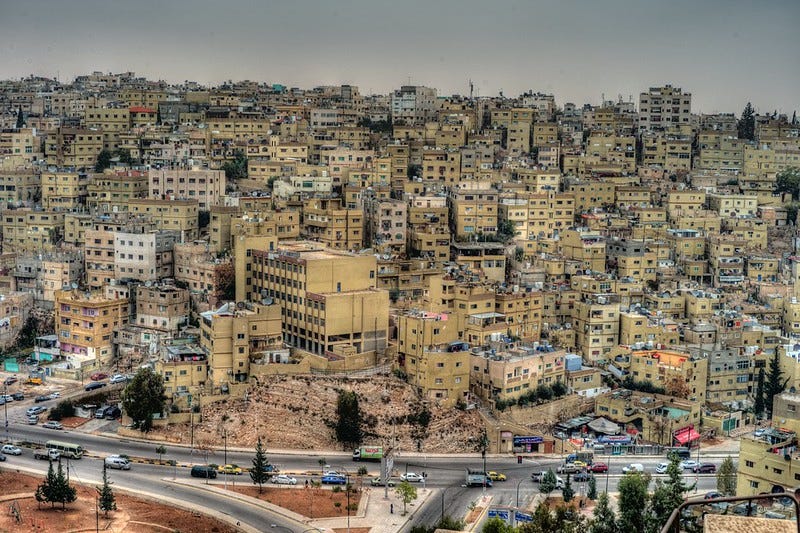

Jordan, in the Middle East is an uninhabitable landscape. Yet since 2000, its population has more than doubled. Refugees from neighbouring countries continue to seek sanctuary, placing ever more pressure on an environment that isn’t able to support its population.

Severe water scarcity occurs when there is an annual renewable water source of only 500 cubic metres per person. In Jordan, it is just 100. What little fresh water there is comes from depleted aquifers, some of which are declining at a rate of 10m per year.1 Most is used for industrial agriculture under rows and rows of plastic, irrigated by salty water from sewerage plants. Rainfall almost immediately evaporates, making the soil more saline than it already is. Its Mediterranean climate is becoming more extreme. Temperatures, in some areas, reach 50˚C. A vast section of the population lives in the city of Amman, heavily polluted from insecticides, the burning of the city’s waste, and desert dust. The majority of the land is either desert or rock.2

When Geoff Lawton landed in Jordan in 2001, he didn’t expect the challenge ahead. Contracted for three years as a permaculture consultant, he had taken on the task of turning ten acres of saline desert into an oasis. Despite more than fifteen years of experience, even he wasn’t sure the project was feasible. It was hard to have hope when the location was just 2km from the Dead Sea, and the land so overgrazed it had degraded to dust.

Permaculture is a form of design based on observing patterns of nature. It is a way of planning your home and land to create a sustainable and regenerative system. Through a holistic, closed system design (one in which the outputs, like waste, are reused as inputs to feed the system), Geoff aimed to speed up the process of ecological succession3 by restoring the soil in which plants could grow.

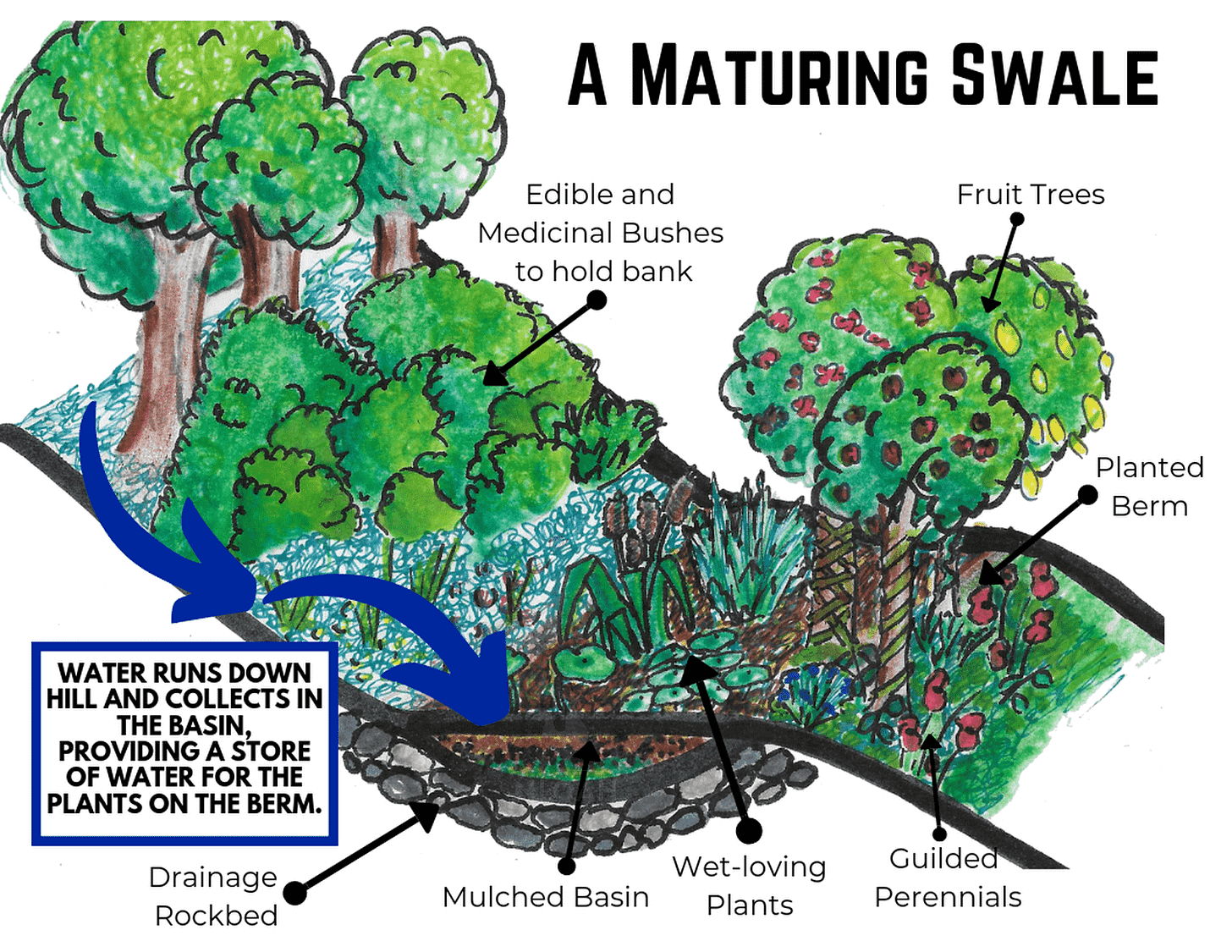

The project started by harvesting every single drop of water that fell on the ten acre project. He and the team dug swales - large trenches which are positioned on the contours of the land so that run off from rainfall higher up the land is fed into the swale lower down. The swale and earth banks on either side are heavily mulched to prevent water evaporation. Then, pioneer trees, seemingly without any productive benefit, are planted. More productive fruit and nut trees and other edibles are placed under their canopy.

Here’s Geoff’s story, told in less than 6 minutes:

How exciting, not only to have the last laugh, but to discover you have inadvertently created a means for reducing soil salinity!

Ain’t fungi great!?

An interesting Portuguese study tested different types of white-rot fungi on soils varying in their degree of salination and organic make-up. Although they weren’t explicitly testing for reducing soil salinity, they hypothesised that the addition of fungal exudates (e.g. the waxy substance that Geoff talked about in the video above) would increase germination rates and crop yields for lentils. I can’t pretend to understand the science, but it concluded:

Rot fungi can play a role in the process of recovery of salt-affected soils. Due to their high salinity tolerance, they may thrive in these environments producing and releasing nutrients to the soil, which may be then used by plants in the vicinity to subsist.

In some cases, the addition of rot fungi increased germination rates by 60%.4 It seems The Greening the Desert project had discovered something important.

Unfortunately, funding only lasted for three years, and although several local people had been trained in permaculture methods, when Geoff, and his wife Nadia, returned in 2008, the project had been subject to mismanagement. Despite this, the perennial plants continued their function of contributing to greater soil fertility and it wouldn’t have taken much for the project to become viable again. Locals could see the regenerative impact of the site, but didn’t understand it well enough to maintain it. However, the Lawtons’ hope for it to remain a demonstration project wasn’t happening.

With a view to establishing a permaculture organisation dedicated to demonstration and education in Jordan, Nadia pushed for a ‘sequel’ to the first Greening The Desert project, one they could manage and oversee themselves. There was sufficient latent interest and enthusiasm from the first attempt for people to want to know how to manage a similar site more productively.

With the support of Muslim Aid, Australia, they acquired a small site, not too far from the first. It is maintained by income generated from short and longer term permaculture courses on site.

The design began with a large water tank on top of a toilet block. Human manure from dry compost toilets is incorporated into the system as garden compost. Grey water goes through to reedbeds which are high enough to gravity feed filtered water to trees below. No water is lost from the site. Swales on the contours of the land are also used to capture rainfall and at the bottom of the system, rabbits and chickens add additional compost, which feeds a shade-covered kitchen garden. Surplus goes to food forest trees and to the nursery where it is sifted for potting. A roof-top garden is facilitated by wicking beds, which reduce the need for watering by up to 80%. Plants are watered from beneath the soil, which decreases evaporation. After the first week of planting, wicking occurs, a natural capillary action of moving water to the plants’ roots.

People attend the Lawton’s permaculture courses from all over the world, but they have also attracted high profile students from within Jordan. Many have gone on to create permaculture projects of their own.

Mohammed Ayesh, a researcher for the National Centre for Agricultural Research and Extension encourages farmers to harvest water, compost and utilise other permaculture elements in their practice as his research shows improved yields, in addition to other environmental and human benefits. On the basis of his findings he created and distributed a small instructional booklet for specialists, farmers and others with an interest in implementing permaculture design. He continues to research and teach in Jordan.5

The Jarash Ministry of Agriculture encourages a return to a rain water harvesting system which had been practised in 1956, a structural system that Geoff Lawton had noticed during his first years working in Jordan.6

Sameeh Al Nuimat, who lives in the small village of Bayoudah, has enthused 400 households in his neighbourhood to harvest rain water, repurpose their grey water, compost and enhance their food security. It was the only site in Jordan which didn’t lose an olive harvest to severe drought in 2008. The success of this demonstration village has led to plans for incorporating permaculture design into five other rural villages.7

The Lawton’s personal project has matured. Nadia’s desire to found the organisation Permaculture Middle East was realised and she has a lot of interest from women in the Dead Sea area. By educating women, they are improving the chances for food security in the area for the next generation. The Greening the Desert site continues as a thriving demonstration and education site.

Geoff believes that permaculture is the only hope for the future. He goes as far in his belief to say:

“All the problems of the world can be solved in a garden.” (Geoff Lawton)

All the problems of the world is quite a stretch, but there is evidence for permaculture’s contribution to mitigating the effects of climate crisis through regenerating degraded soils.

Healthy soil is essential for drawing down atmospheric carbon. When achieved purposefully, it is a process known as ‘carbon farming’, which is associated with making farms more resilient against climate change. In the African Sahel region, regenerative agriculture is an adaptive strategy to cope with the rapid decline of the rainforest. Farmers have had to shift to practices more suited to savannah and desert. In the Sahel, “natural regeneration and evergreen agriculture have been spreading at a phenomenal and unprecedented rate” (Eric Toensmeier, 2019). He stated that this form of farming has powerful mitigation benefits too. So much so, that since the Paris Agreement it is now seen as part of the solution. The caveat is that the process isn’t moving fast enough. However, it could be helped by a change in global policy. Of 700 billion dollars of agricultural subsidies world-wide, only 1% funds environmentally-friendly agriculture.8

While the Permaculture’s beneficial impact on the environment can’t be overstated, its contribution to social justice shouldn’t be ignored either.

[Permaculture] sets expectations for the ways communities organised themselves to make decisions, manage conflict and achieve larger goals like providing education.(Christina Ergas, 2021)

Environmental Sociologist, Christina Ergas, undertook two in-depth studies of collective permaculture communities, one in the Pacific northwest and one in Havana, Cuba. Her research suggested that permaculture, which “sets expectations for the ways communities organise themselves to make decisions, manage conflict and achieve larger goals like providing education”, contributes both to fully inclusive participatory democracy and to greater social justice.

Key groups are differently affected by climate crisis, with underprivileged groups being disproportionately adversely affected.9 Permaculture is a means for redressing the balance by enhancing farm resilience and improving food security. The farms in Christina’s research were essentially both workers’ cooperatives. Because of permaculture’s ethic of sharing surplus, the rate of consumption in the two communities was slowed. In the Cuban study, surplus was converted into wages, which were good in comparison to the country’s average wage.

Although my research focused on only two small communities, I believe the principles of permaculture offer an important model because they address both the environmental and social challenges posed by climate change.

Permaculture holds powerful lessons that could guide many countries to save resources and cut emissions, thus finding a balance between production and consumption.10

Perhaps Geoff Lawton isn’t too overly optimistic about permaculture’s potential after all?

Not all permaculture projects are documented, but Geoff’s goal of a world-wide movement is well-established. The current attempt to document a map of permaculture sites across the world lists the number of projects at 2751.11 As this is self-referential, it’s not likely to include them all. Additionally, community and forest gardens and various architectural projects, which may utilise at least some of the principles, are also not likely to be listed.

Getting started with Permaculture

There is very probably a teaching site near you, but courses tend to be expensive, intensive and time-consuming. My own experience, however, was that a two-week intensive was absolutely life-changing and was probably the inciting point for this newsletter, even though the course was 11 years ago. At the Eco Design Hive, a beginners’ introductory course is available online. It is free, but founder, Heather Jo Flores, appreciates a gift of whatever you can afford. I’ve found Heather to be a highly thoughtful and critical practitioner, and I highly recommend a read of some of her articles.

Embers

Recently, I’ve been very inspired by

’s response to a drawing lesson in the street from who is the artist behind , a candid snatch of urban life I particularly enjoy. I also love ’s emotive stick-figure sketches in . Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve found myself looking at an empty sketchbook and an ink pen. I had that blank look from a blank page and went blank. Then I got an idea, popped over to Cricklewood, where lives chronicling nature in a journal. She’s pretty good at it! An hour or so later, my blank sketchbook has a title page thanks to, but doesn’t look quite as pretty as Susannah’s. I haven’t got a clear intention for it yet, but will share as the sketchbook progresses.Up Next:

In the first post for this newsletter, food was declared as a unifying language to cut across age, income and culture. In that vein, I am going to continue with the theme of food security and sovereignty for the next few posts. Next week, we’ll travel to Burkina Faso, for two stories in one, to learn how a traditional method of farming was revived in response to dire environmental change and triggered an exponential movement - the one referred to by Eric Toensmeier in the discussion above.

Unicef for every child: Jordan (2022) https://www.unicef.org/jordan/water-sanitation-and-hygiene. Date accessed: 11/08/2023.

Greening the Desert II (2015) Date accessed: 11/08/2023

Ecological succession is the process, in the absence of human activity, by which nature gradually replaces one species with another until a state of stability is attained.

Borges, J., Cardoso, P., Lopes, I., Figueira, E., & Venâncio, C. (2023) Exploring the Potential of White-Rot Fungi Exudates on the Amelioration of Salinized Soils. Agriculture 2023, 13(2), 382; https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13020382 Date Accessed: 14/08/2023

Permaculture Research Institute (2015) Greening the Desert II (see note 2)

ibid.

ibid.

Toensmeier, E. (2019). CARBON FARMING: A SOLUTION TO CLIMATE CHANGE? Journal of International Affairs, 73(1), 231–236. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26872793 Date accessed: 12/08/2023

Simmons, D., (2019) What is ‘climate justice’? It begins with the idea that the adverse impacts of a warming climate are not felt equitably among people. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2020/07/what-is-climate-justice/ Date accessed: 13/08/2023

Ergas, C. (2021) An environmental sociologist explains how permaculture offers a path to climate justice. https://theconversation.com/an-environmental-sociologist-explains-how-permaculture-offers-a-path-to-climate-justice-165938. Date accessed: 13/08/2023

Permaculture Research Institute. https://permacultureglobal.org/projects Date accessed 14/08/2023