We’ll do anything to watch a sunset on a clear summer day at the beach. We’ll stand and stare and remain silent, as suffused shades of orange stretch over the horizon. Meanwhile, the sun, like a painter who keeps changing his mind about which colors to use, finally resolves everything with shades of pink and light yellow, before sinking, finally, into stunning whiteness.1

The Cliffs of Moher are strikingly breathtaking any time of the year. The landscape can be violent, dizzying, but on a night like this, equally calm and peaceful. We’re alone, the last people at the edge of the earth, without the sight of distant fishing boats to suggest otherwise. We’re a party of six, who had earlier squashed into the limited seating of small antique car, driven by someone without insurance who we learned later could barely see the road. It was the end of August, and with the remaining balmy weather we want to make the most of the last of the summer wine. We hadn’t plan to stay long, but the drama of location grips at our soul, keeping us bound to the landscape and the joy of being young and alive. The power of the place silences our own exuberance. To leave would be a sacrilege to its beauty. As silvery glitter pockmarks the sky, we drift off to sleep.

Dawn. I wake to the most haunting sound I’ve ever heard. Padraig has moved away to the cliff edge to play the uillean pipes. Other members of the party rise. Their sleepy bodies shake off an awkward night of sleep. I shiver. My friend lifts up her arm in front of me. Its fine hairs stand to attention and pull her smooth skin into an even layer of goosebumps. A shared moment of extraordinary beauty. A peak experience.

The most beautiful thing that you ever seen is even bigger than what we think it means.2

On Instagram, one woman has made it her life’s purpose to actively search out a thing of beauty daily. She claims it has changed her life and encourages her followers to do the same. Here, on Substack, in your own words and images I perceive this same human keening for the experience of beauty. Unlike the Instagram woman who finds beauty in consumables, many of you find it in nature and convey its beauty in your creative enterprise.

Such an one, as soon as he beholds the beauty of this world, is reminded of true beauty, and his wings begin to grow.3

Yet beauty is incredibly difficult to define and understand. For centuries the best minds have grappled with its meaning. More interesting is not what it is so much as why it matters. While Plato views the recognition as a form of love, itself a kind of madness, psychologists have shown its benefits for mental health and self-development. As part of its Turning Points series, the New York Times asked writers, conservation photographers, a physiologist, fashion designers, an actor, a chef, an astrophysicist, and an education activist why beauty is important in their lives. For most, the experience of beauty gives life meaning: the experience of love, the feeling of being at one with the world, the questioning of how a life should be lived, a pursuit for truth, a deeply spiritual power, the essence of existence, a power for transformation, and a force for connection.

When we become aware of life’s beauty, that’s when we are most alive.4

German psychologist, Gustav Fechner was one of the first to test beauty in the laboratory. In 1876, he discovered people have a preference for rectangles with sides in proportion to the golden ratio.

Imagine a line divided into two parts. If the whole length of the line is divided by the longest part of the line, in a golden ratio this is equal to the long part divided by the shortest part of the line. So, let’s say a line is 100 cm long and you divide it into two parts, the first with a length of 72, the second a length of 28:

100/72 = 1.389

72/28 = 2.571

These are clearly not the same, so are not an example of the golden ratio.

However, try this:

A line of 100 cm is divided into two parts, the first is 61.8 cm, which makes the second part equal to 38.2

Then

100/61.8 = ?

61.8/38.2 = ?

If they are the same, then you have an example of the golden ratio.

The answer to both is 1.618… , also denoted by the Greek letter Phi (ɸ), and is a ratio, Gustav found, the brain prefers to any other. Although this specific finding wasn’t independently replicated, it is still argued there is beauty in the golden ratio, so much so that artists and architects incorporate its golden allure into their work. The ratio has also been termed divine, reflecting the human experience of beauty as beyond a pleasant experience to something more spiritual.

The pursuit of beauty gives rise to questions about whether there is an inherent objective beauty to specific objects or if is an entirely subjective experience. If subjective, then why are some phenomenon so universally perceived as beautiful? If, say a sunset, has objective beauty, then what is the quality that enables us to perceive its beauty? Does it conform to the golden ratio, have symmetry or some other quality? Then what is it about our neurology that contributes and gives value to the experience? While a great deal of work has explored the aesthetically pleasing nature of various objects and their proportions, it wasn’t until more recently that we’ve been able to image the possible neural correlates for experiencing beauty. Is there a part of our brain which responds to beauty? Do we have a beauty centre?

In a relatively recent study conducted at Tsinghua University, Beijing, researchers, rather than add to the chaos of findings in answer to this question, instead conducted a meta-analysis. They compiled the data from 49 beauty experiments with a total of 982 participants. The studies would go something like this:

Participants were asked to view and rate a variety of paintings into beautiful, neutral or ugly. The same paintings were then viewed while the participant was in a fMRI scanner.5

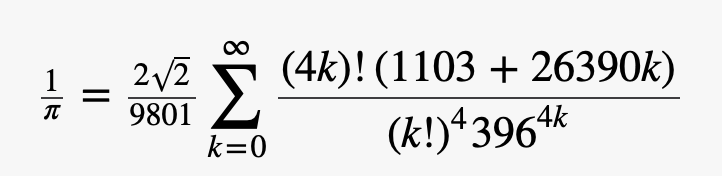

Included in the Beijing study were experiments with both paintings, like the above, and with human faces. They found that both beautiful faces and beautiful paintings activate well-defined brain regions, but NOT the same regions. Which part of the brain was activated was dependent on the medium, not the experience of beauty. On the other hand, a study conducted with 15 mathematicians found that mathematical formulae rated as beautiful activated the same region as has been found with beautiful paintings.6 To date, it would seem, our understanding of the human experience of beauty is in very murky waters.

Incidentally the latter study found that Leonhard Euler’s identity was most consistently rated as beautiful. It looks like this:

And the most ugly?

To me this seems unsurprising, one looks more elegant than the other. But I can’t claim to understand either. This issue of separating understanding from beauty was the most challenging aspect of the study. To account for this the researchers included non-mathematicians and found that some equations displayed forms that were more aesthetically pleasing even if not understood, engaging the same neural activity as if seen by a mathematician.

The researchers conclude with a quote from Dirac (1939):

the mathematician plays a game in which he himself invents the rules while the physicist plays a game in which the rules are provided by Nature, but as time goes on it becomes increasingly evident that the rules which the mathematician finds interesting are the same as those which Nature has chosen …7

Future mathematical work, he proposed, should be influenced by considerations of mathematical beauty. The concordance between art, mathematics, nature and the human experience of beauty is something I’d like to explore in greater depth, and though I’d planned to undertake something more concrete for the next series, this current series on the aesthetic of transience has inspired a desire to delve deeper into the concept of beauty. And so it will be the theme of the next series. I hope you’ll stay with me!

Embers

When I’ve gone travelling to Portugal’s more urban centres, I’m often stunned by the way decrepit spaces are enlivened by murals, some offering a sense of the town’s cultural history.

André Aciman, in interview for the New York Times.

Lizzo, My Skin. https://genius.com/Lizzo-my-skin-lyrics

Plato, Phaedrus. Cambridge University Press (p. 92)

Constance Wu in interview for the New York Times.

This study was conducted by Kawabata, H., & Zeki, S. (2004). Neural correlates of beauty. Journal of neurophysiology, 91(4), 1699–1705. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00696.2003. I am unsure if this was a study included in the Chinese meta-analysis. The results were positive, the perception of a beautiful painting was associated with activity in the orbit-frontal cortex.

Dirac, P. (1939). The relation between mathematics and physics. Proc. R. Soc. Edin. 59, 122–129. cited in the above article (see note 6)

WOW... ON SO MANY LEVELS DEEP! Safar, you are one in a million, and I'm glad to read you. Keep up the great work.

Is beauty subjective? The old joke applies here: One man's wife is another man's passion : )