To get coal from a mountainside, strip miners dig in at the level of the seam, circling the hillside with an indented, treeless ring. Because of strip mining’s destruction of the natural environment, regulations have been imposed, limiting it and requiring reclamation of the land whenever it’s done. Both strip mining and dynamite sculpting alter the mountain on which they work, the latter probably more than the former. Yet, while strip mining is seen as something to be avoided whenever possible, people widely approve of the Crazy Horse sculpture, flocking to see it . . . . A question comes to mind: what’s the difference between the two forms of mountain carving? (Peter Humphrey, 1985, p. 6)1

The Crazy Horse sculpture began in 1948 and is a monument to the memory of the former Lakota leader, Crazy Horse. It stands in the Black Hills of South Dakota and at 641 feet long and 563 feet high, it is unfinished, but enjoys a commitment to completion.2

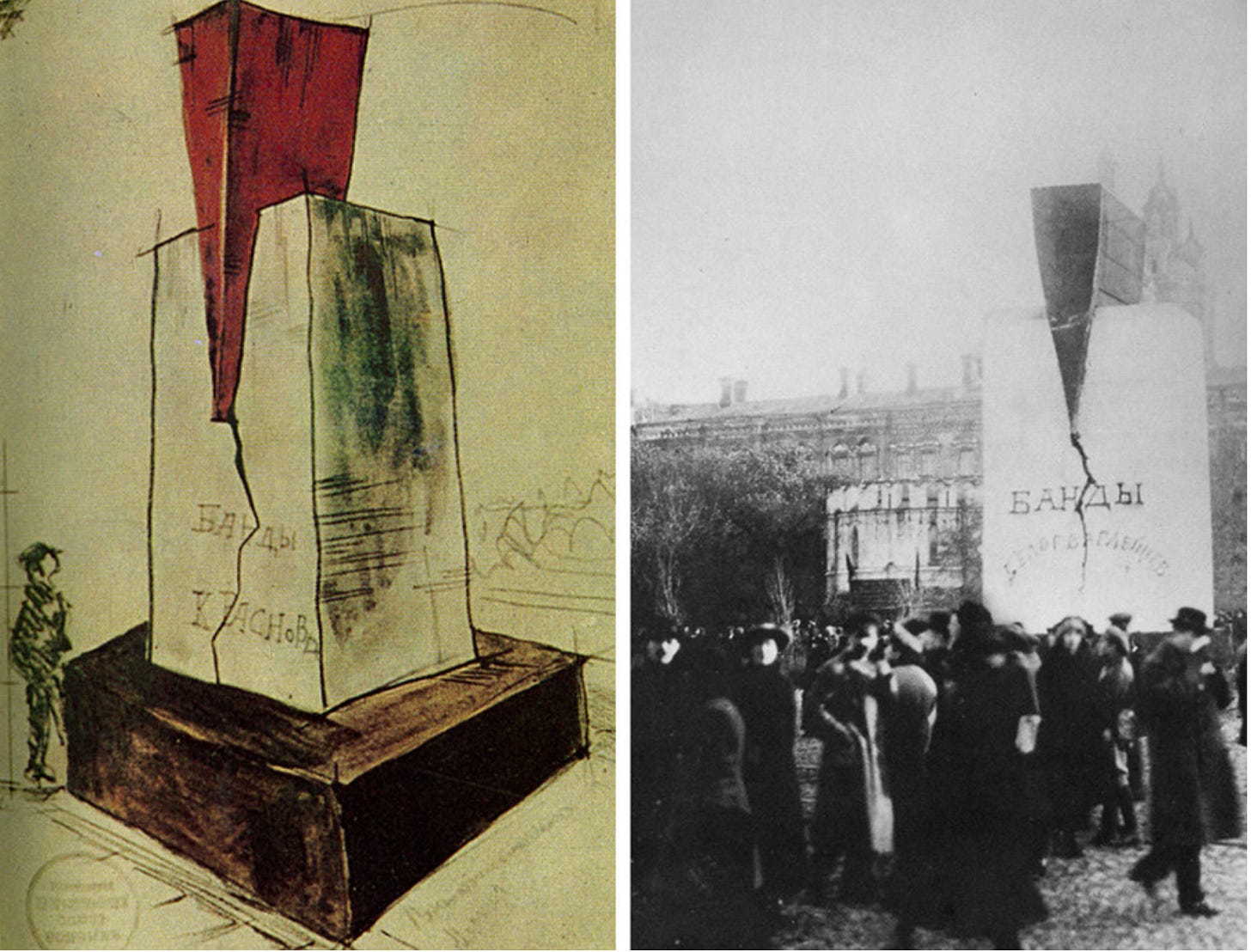

Bulgarian artist, Christo’s passion for wrapping objects began after his father had been falsely arrested for sabotaging a nationalised textiles factory. His mother’s interest in art then drew his attention to the post-1917 Russian art movement dominated by the spectacle of decking the streets with colourful geometric forms.3 He went on to study art, and as a student was employed by the state for propaganda art, which included displaying scant harvests to look ample for western visitors as they passed through Bulgaria by train. This entailed, as an example, covering distressed hay bales in fabric and rope.

He started small, a bottle here, a shoe there - objects covered in various textiles, until he took on the environment itself. By now though, he had an accomplice in Jeanne-Claude, who liked to talk about the passion of their relationship as much as she did their art.4 In 1968, they employed a team of art students and teachers, architecture workers, 15 rock climbers, a project leader and an engineer, along with a million square feet of fabric and 35 miles of rope to wrap one and a half miles of Australian coastline.

They created Wrapped Coast - One Million Square Feet, which was then the largest piece of art ever made. Unlike some other pieces they later made, they never explained the work, giving rise to the question of meaning and purpose. In interviews, many years later, it seemed nothing more than because they could.

We create a gentle disturbance for a few days.

We make beautiful things, unbelievably useless, totally unnecessary.

Christo, in interview5

The work is given meaning by the viewer with one interpretation being that by concealing an object, more is revealed. This is something Christo disputed. In the work below, Valley Curtain, he claimed it wasn’t at all about concealment. All you had to do was lift the veil and pass through to see the other side. It was more about creating a new relationship with the valley.

The most important aspect of the curtain was the ability to mentally penetrate that membrane, to be able to pass through that obstruction realising a new relationship has been created.6

At Wrapped Coast, I think I would have preferred to see its raw, ragged, and violent beauty, rather than its ‘taming’. To me, it portrays an unforgivable disrespect for its sea life. It is only in the above photograph that I see anything of its aesthetic appeal, which says more about the photographer’s perspective than it does of the original artist.

Valley Curtain was erected in Colorado four years after their wrapping of a coastline. It took two years, with as similarly large a team as Wrapped Coast. Like Richard Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, the documentation process was as much part of the art as the final installation. An initial attempt in 1971 met with failure, high winds tearing fabric moments before completion. The second attempt was more successful, but was to last just twenty-eight hours before it had to be dismantled on account of a gale7 - too short a time, for an operation which “required over 23,000 square meters of fabric to be hung on four steel cables, fixed on each slope at both ends of the valley to large concrete bases, weighing 200 tons each”.8 Wrapped Coast also had suffered when a storm ripped the fabric and a segment had to be redraped three quarters of the way through construction. To me, this feels like nature saying ‘No!’

For Christo, the meaning of the partnership’s work lay in the process and not the product. Once finished, it ceased to be art.

The duration of the completed project is completely irrelevant. … How much time it stays up for the public is not a crucial question. … If the wind happens to destroy the fence on the second day, then that’s how long it will stay up.

The materials themselves are very temporary and are not designed to remain standing for any considerable length of time. The work on the fence has gone on for years; and when it is finished for the artist, it does not exist anymore.

Christo in interview during the construction of Running Fence, a 26 mile long fence from Petaluma, California to the Pacific Ocean.9

Despite the apparent frivolity of Christo’s and Jeanne-Claude’s land art (they funded it themselves), there is a more serious intent behind their work than would seem from his statement above. Christo, given his education in the eastern bloc is always conscious of the social and political landscape of the environment in which they work.

The most important part of my projects are that they are so great in complexity that I cannot speculate on what the project means at all times. All of my thinking, for example, revolves around the environment - not only the landscape or the hills, but the changes in the social and political environment as well.10

In Running Fence, his choice of landscape was consistent with this intent. He made use of different types of land, urban, suburban and rural, to emphasise the social and political conflicts in the use of land by different people. In the making of the construction their own negotiations with city administration and environmental assessment personnel was as much a part of the art as the final fence.

My purpose today wasn’t to consider so much the ethics of this form of environmental art, as important as that is, but of whether it is an aesthetic affront to nature.

This question was raised by philosopher, Allen Carson. Environmental art is distinguishable from sculptures you might see in a park in that the site is part of the art. Sculptor, Henry Moore, for example, had a deep relationship with the landscape and conceived of placing art in nature. However, he placed sculpture in the landscape, but the items were created without a particular landscape in mind. They could be sited equally well anywhere.

On the other hand, land/environmental art is distinguishable by the site “being part of the content of the work".11 The way nature is incorporated into the work has led not only to questioning the environmental impact, but also its aesthetic indignity to nature.

[The artists] are engaged in an aesthetic affront to nature that goes deeper than the scientific assessment of environmental implications.12

While I question Wrapping Coast in environmental terms, and even its aesthetic qualities, that is not the same as it being an affront to nature. Allen Carlson argues the recognition of an aesthetic affront to nature requires an appreciator of the indignity, as nature itself cannot recognise it.13 The philosopher goes on to say having a human appreciator of the affront is acceptable. I could, for example, insult, affront or oppose upon you, and you may not recognise it.

Many of the earthworks have required bulldozers to create (e.g. Walter De Maria’s Las Vegas Piece, Michael Heizer’s Double Negative). The result is akin to the result of a mining operation. Some other works “resemble the aesthetic consequences of certain kinds of industrial pollution”.14 In other words, they are eyesores.

This view has been contested. Just because industrial scars and scars for art are identical, does not mean environmental art is an aesthetic affront to nature. The context of what they are matters. To say the bulldozed scars are an aesthetic affront is to not consider the kind of object they are. Industrial scars lack aesthetic value, but those appreciated as art may have aesthetic qualities. The appreciation has to be appropriate.

I disagree. In 1919, Marcel Duchamp created L.H.O.O.Q. which was a mustached and goateed version of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The inscription L.H.OO.Q. sounds like elle a chaud au cul which he himself translated as there is fire down below. Avoir chaud au cul was a derogatory term for a promiscuous woman. Allen Carlson uses the example to illustrate how Duchamp managed to denigrate the original work - creating an aesthetic affront to the Mona Lisa. In relation to environmental art then:

… the affront is not simply a function of the appearance of an object; it is a function of changing an object’s kind and thereby altering its aesthetic qualities.15

The above examples of art, and those discussed in last week’s post, could then be said to be an aesthetic affront to nature.

The most extreme case of this is Michael Heizer’s, City.

I will leave you to ponder City’s ethical and aesthetic affront to nature.

Next Week

Last week, I actually promised City as the subject of today’s post. However, already conscious of word count, this is postponed until next week, as we continue this dive into the ethics and aesthetics of land art.

Embers

This week I spent time with the world and art of

. It’s a gentle space for learning and appreciating. Her experiments into the behaviour of different watercolour pigments are extraordinary, and she often shares a little known art process which I find fascinating. However, the post which most caught my attention interwove an artist and a dying magnolia into a reflection on the lessons to be gained from gardening.“Matter aggregates, into something beautiful.”

Thank you for reading!

Cited in: Lintott, Sheila (2007) 'Ethically Evaluating Land Art: Is It Worth It?', Ethics, Place & Environment, 10:3, 263 - 277 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13668790701567002

Here you can follow the progress of the sculpture since its inception: https://crazyhorsememorial.org/story/the-mountain/

Jelavich, P. (1995). The Wrapped Reichstag: From Political Symbol to Artistic Spectacle. German Politics & Society, 13(4 (37)), 110–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23736267

op.cit.

Garoian, C., Quan, R., & Collins, D. (1977). Christo: On Art, Education, and the Running Fence. Art Education, 30(2), 17–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/3192172

https://www.artesvelata.it/christo-nouveau-realisme-land-art/ (translated by DeepL)

see note 6

op. cit.

Art critic, Elizabeth Baker quoted in: Carlson, A. (1986). Is Environmental Art an Aesthetic Affront to Nature? Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 16(4), 635–650. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40231495

Donald Crawford also cited in the paper above (see note 11)

I can already see some of you protesting at this statement. To accept as a truism that nature cannot recognise an affront is a limited view.

Carlson, A. (1986). Is Environmental Art an Aesthetic Affront to Nature? Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 16(4), 635–650. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40231495

op. cit.

I love the argument (intended) in this essay Safar…

For reasons of environmental disruption, whether that be to fauna, flora, or any other of natures own art, unless these (rather incomprehensible) errections, coverings and earth movements are constructed in complete harmony and sympathy with the nature surrounding and living upon it, I see it rather like the hunter glorifying his kill by asking for a photo of said dead creature laying in front him and his weapon. I cannot condone such behaviour. Likewise with these vast works of art(?), whilst I find some aesthetically pleasing, at what cost?

Perhaps I am narrow minded in this, old fashioned even but truly, who is the beneficiary… ?

Thank you for visiting my substack and sharing it! I am so glad that the post on Rita’s magnolia meant something to you. I was very new to writing again when I wrote that.

Again, fascinating echoes back to myth training in Landscape Architecture in your main post - the profession was thought to be ‘being the advocate and spokesperson for the landscape’, os writing reports on whether something was or wasn’t an affront to the aesthetics of nature was part of the job. And of course the landscape was pretty mute on its own aesthetic potential.

I always found the clash between the aesthetics of the landscape and the functioning of the landscape odd - for example the public would often object to something like a barrier that kept invasive species out because it was ‘ugly’, and interrupted the landscape. Yet it was improving so many of the ways the landscape was creating habitats for endangered animals,,say.

As part of one of the university projects, we were to make a piece of land art, once. I made a sort of a pile of fallen weed species flowers with a wrapping of some shiny paper (which I was going to remove at the end of the day). Then I hid to see what would happen. The first person to come across was a man who was instantly enraged and hit its repeatedly with a stick until everything was scattered. He definitely thought I was committing aesthetic affront.