Robert Scull’s initial reaction to receiving the above letter was that “he [Michael] was absolutely crazy”.1

Robert was married to the wealthy Ethel Redner who had inherited a business from her father. They renamed it Scull’s Angels and although it sounds more like a spin-off from a motorcycle gang, it was a highly successful taxi company. The couple shared an interest in collecting art, and between them, were able to support pop artists such as Andy Warhol. They were as much the subject of the art as they were its benefactors.

Their collection gradually diversified to include abstract expressionism and it was during this time that Robert received the letter which was to change the couple’s direction from collectors to patrons of art.

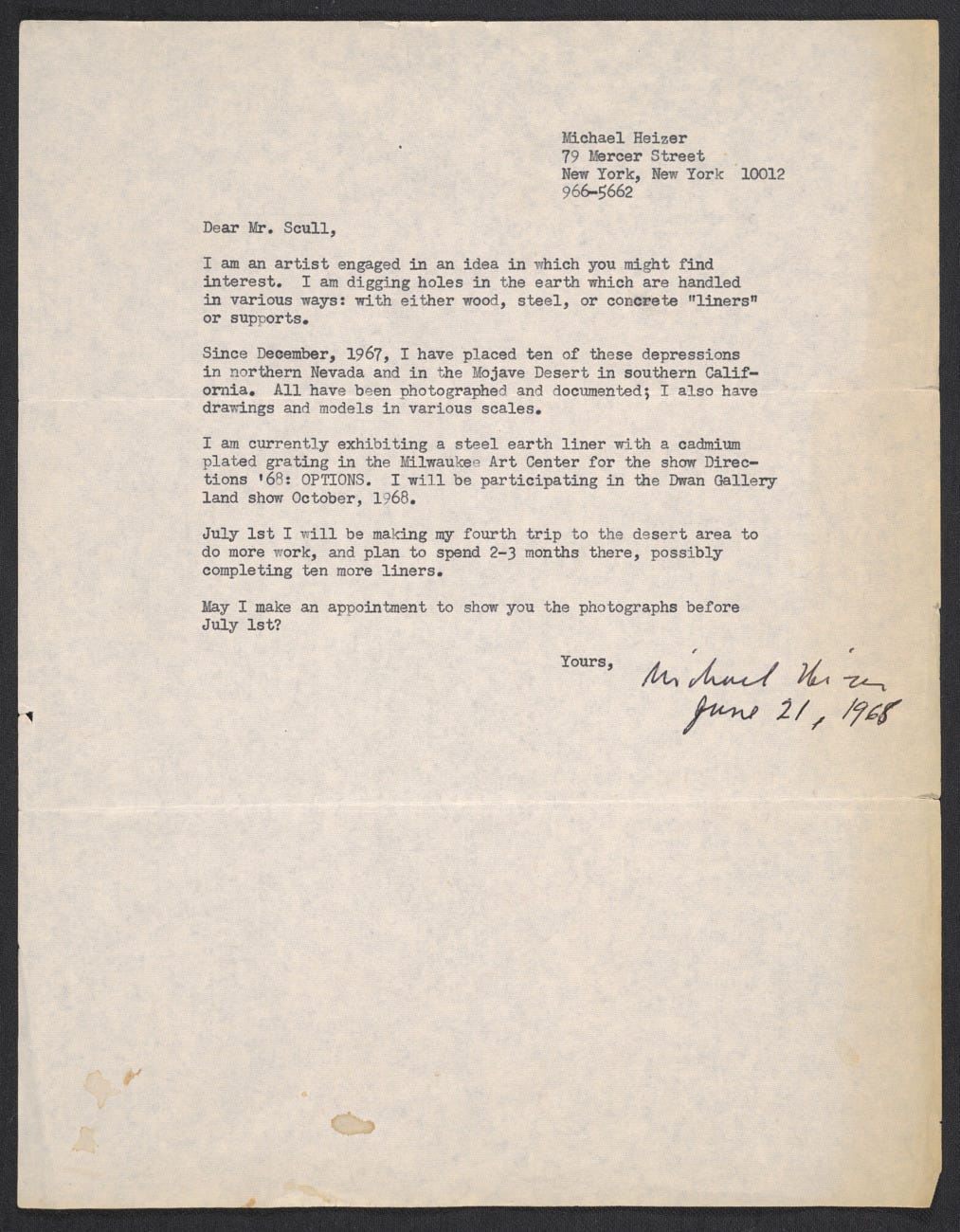

Dear Mr. Scull,

I am an artist engaged in an idea in which you might find interest. I am digging holes in the earth which are handled in various ways: with either wood, steel, or concrete “liners” or supports.

Since December, 1967, I have placed ten of these depression in northern Nevada and in the Mojave Desert in Southern California. All have been photographed and documented; I also have drawings and models in various scales.

I am currently exhibiting a steel earth liner with a cadmium plated grating in the Milwaukee Art Center for the show Directions ‘68: OPTIONS. I will be participating in the Dwan Gallery land show October, 1968.

July 1st I will be making my fourth trip to the desert area to do more work, and plan to spend 2-3 months there, possibly completing ten more liners.

May I make an appointment to show you the photographs before July 1st?

Yours,

Michael Heizer,

June 21, 1968

Despite his misgivings, Robert agreed to meet the artist. As they talked, Michael outlined his vision for Nine Nevada Depressions, a series of land sculptures over a length of relatively inaccessible desert of 540 miles. Robert wondered who would ever get to see it. The artist’s response was that it would be no different to viewing the Mona Lisa which would require a flight, connecting transport and a flight of stairs. Except in his case, you would need a helicopter.

Robert agreed to fund the work and as the bills piled up, he made that helicopter journey with a Life magazine photographer. The experience was overwhelming:

When you land on one of those dry lakes thirty miles outside of Vegas, there’s no more city, there’s nothing but miles and miles of desert. And when I saw this piece of sculpture in the ground … surrounded by a world of nature, I began to realise that this is some of the most important sculpture in the world; and that it’s not necessary that I be able to take it home to Fifth Avenue.2

Although he couldn’t take it home, he stated that ‘owning’ it provided him with a sense of kinship with it. Michael Heizer and Robert Scull remained firm friends, corresponding regularly throughout their lives. They shared an appreciation for the radicalism of land art, and were increasingly ambitious in their vision.3 Michael was to take his own concept to the extreme when, in 1970, he began City, a monumental work inspired by archaeological sites he’d visited with his father as a child.

It took 52 years to finally open to the public though the artist still doesn’t consider it to be finished. At more than a mile and a half long, City is generally regarded as the largest sculpture ever to have been created. While it makes use of local sand and gravel, much of its construction entailed imported materials. The scale of City was beyond the generosity of any individual sponsor, the entire project estimated to have cost 40 million dollars. A trust was established not only for completion of the piece, but to ensure its posterity. It is composed of a series of complexes, each built at specific point in time dependent upon continued funding.

Complex One (below), the first element to be built, was inspired by the step pyramids of Egypt.4 It is an optical illusion. When viewed straight on, the shapes align to frame the structure so that it almost appears like one of his two dimensional works. This stage of the project was almost entirely built by Michael’s own hands.5

Complex 2 began in 1980. It is quarter of a mile long. Its surface is irregular and incorporates a triangular and rectangular projections alongside upright steles that weigh up to a thousand tons each and stand up as much as 21 metres high. It was inspired by a description from his father’s book about La Venta in the Yucatan which also had stones shaped like those in Complex 2.6

Given the construction of City was a major factor in the breakdown of his relationship with his wife, and that it almost killed him, it begs the question of why. Michael has no romantic notions about the piece. The site wasn’t selected for its beauty, but because it was cheap; unlike other land artists who incorporated background mountains as a visual element in their work, the distant hills beyond City are accidental, never intended to be a feature of the design.

All these so-called experts try to say my work is about the West, that’s it about the view (sic). They don’t know what they’re talking about. I came for the space and because it was cheap land. I don’t care if you see the mountains. … The sculpture is the issue, not the landscape.7

The art is a fusion of ancient with modern and futuristic forms. As well as the angularity of the different complexes, arcs and curves connect the various elements. It is alien to the landscape, yet embedded within it. Even at the perimeter fence it is difficult to see and there is no vantage point from which it can be photographed in its entirety. When a group of skateboarders tried to access the site as a magazine piece, they were unable to get more than a glimpse of the art.8

It has to be experienced in time and space - over time, and distance.9

City was hidden away for decades; until recently, its location a mystery. Michael resents those who use arial means to see it. “Flying over it squishes the Gestalt. It’s supposed to be about a motor-delayed, cumulative observation: you’ve got to walk around it, climb over it and later put it together in your mind and figure out where you were.”10

One complex includes a plaza, constructed below ground level, though not enclosed. Michael Heizer, in previous work, experimented with negative space. Sculptures which take something away rather than add to a space. His most famous work, Double Negative, involved detonating rock to create a long (quarter of a mile) deep trench. He created negative space by taking away tons of stone and rock in the already empty space of the desert - a double negative.11 The plaza is a reiteration of this exploration and of it he says:

The sculpture is partly open because, rather than put you in a box, I want you to be able to breathe. But I also want to isolate you in it, to contain you in it, like in all my negative sculptures.12

Land was his canvas, but not the point of the work. In this respect it could be said to be the biggest ethical and aesthetic affront to nature of all the pieces presented in this series. Additionally, unlike other land art, City has been built with permanence rather than temporality in mind. He wants his work to endure for millennia. Double Negative is now degraded, but he intends to reline it with concrete to preserve it for the future. And in City, the construction includes military grade steel:

Incans, Olmecs, Aztecs - their finest works of art were all pillaged, razed, broken apart and their gold was melted down. When they come out here to fuck my City sculpture up, they’ll realise it takes more energy to wreck that it’s worth.13

His work might seem at odds with his otherwise great appreciation for nature but he now describes it as part of nature. The hills and valleys of the piece work were designed with light in mind. Changes in the sun’s position create an interplay between light and shadow which mirrors the play of light on the mountains behind it. Sudden drops in temperature create a frost which alters the textural appearance of the piece. When Michael became seriously ill he claimed it was nature that kept him alive.

If you’ve even been in a field of alfalfa with the meadowlarks and the rabbits and the kingbirds … well that’s God moment. You haven’t lived until then. It’s what has kept me alive.14

Visitors are now allowed in to experience the work as intended, a maximum of six per day, at a cost of $150 each. This may not feel right, but it is his and he expects a degree of privacy in relation to the work. Is this any different to a painting in a private collection?

It may not be, but land in a state of nature doesn’t belong to anyone. It seems an incredible arrogance to claim virgin land as one’s own and so seriously deface it whether it be for its resources or for art. Doing so reminds me of the spiritual metaphor of Babylon. It’s time we stopped.

Up Next

Land art within the confines of a gallery space?

Embers

I really want to meet this woman:

More seriously, I enjoyed Joyce’s latest post on thinking about writing as a form of jazz.

is feeling the positive impact of free writing sessions with Allegra Huston who writes Imaginative Storm. I’ve taken a peek, the outcome of her collaborative tutorials are inspiring.Thank you for reading!

Quoted from an interview in GOLDMAN, J. (2011). “MY SCULPTURE IN THE DESERT”: ROBERT C. SCULL AND MICHAEL HEIZER. Archives of American Art Journal, 50(1/2), 62–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23025824

op. cit.

op. cit

op. cit.

op. cit.

For art lovers who might think turning art into a skate park a travesty, they were very respectful of the boundaries and right to privacy of the owners. They knew it was a long shot.

Michael Govan was quoted in: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/17/arts/design/michael-heizers-big-work-and-long-view.html?searchResultPosition=2, Michael Govan was a significant figure in raising funds to enable the completion of City.

Michael Heizer in interview (see note 5)

Quoted by Benjamin Sutton in https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/08/19/michael-heizer-city-nevada-opening-public

Wow, Safar, this is incredible. I’m so glad you closed with that final paragraph. It’s like you read my mind. The arrogance. On the other hand, it does appear that the land worked its magic on him. The reverence of his comment is striking.

What is it about the desert that prompts these megalithic ambitions ... obsessions? 50 years, 40 million dollars! Your posts often launch ponderings about going there (wherever it is you're talking about) and I'm only a long stone's throw from Hiko, Nevada this morning (189 miles) ...

So I went looking for how to make reservations. Nope. Already booked. Thanks, your video saved me a long drive and $150 ... now I'm just left with the pondering. Having just spent a day at Marta Becket's opera house in the midst of nowhere, and thinking over the other passion/obsessions I've discovered along the way, I wonder if it has something to do with negative space, the need to fill in the blank spaces ... or a form of denying death?

I don't think I've written about it here, but you'd probably be interested in Felicity, CA ... the center of the world where Jacques-Andre Istel built a Museum of History in Granite. Here is a flip book I made of that monument ... https://issuu.com/joycewycoff/docs/felicity_center_of_the_world?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ ... thanks again for all the things you give me to ponder on ... and the inclusion in your post.