We tumble out of Rodrigo’s car into the low winter Spanish sun.

We are a group of volunteers working on a straw bale and cob house in the north of the country. Lately, that hasn’t been so pleasant, with torrential downpours and even hailstones shrivelling the skin of our hands and turning them blue. We don’t even have a chance to dry off between sessions. With an unexpected break in the weather, one of the volunteers sneaks away to book an afternoon outing.

A huge cliff towers over us, gnarled trees twisting out of fissures in the rocks. Vultures soar high above us, black sketches in bright blue sky. We look around for the entrance to our destination. We’re at the Cueva del Castillo and though not the most famous location for Spain’s cave art, I’m excited to get my first introduction to palaeolithic paintings.

We clamber up steps toward a small green door, under the porch of a gigantic overhanging rock. It feels ominous. There we meet and follow our guide into the dark, led by his torch. With his mix of acting and repetition, and our combined translation efforts, we manage to make sense of what our guide wants to convey. For two euros each, his tour is good value for money.

The oldest art, a saucer-sized pixellated disk, dated to more than forty thousand years old had been painted by female hands. While the cave is filled with art from the palaeolithic era through to the Bronze Age, our guide focuses our attention on the palaeolithic art which depicts bison, deer, aurochs, goats, a mammoth and human hands.

Not all the art at Cueva del Castillo is representational. In the mix are abstract symbols whose meaning I can only guess at, except they look to me to be extremely architectural, like they are a window into the future. I wonder what they signify.

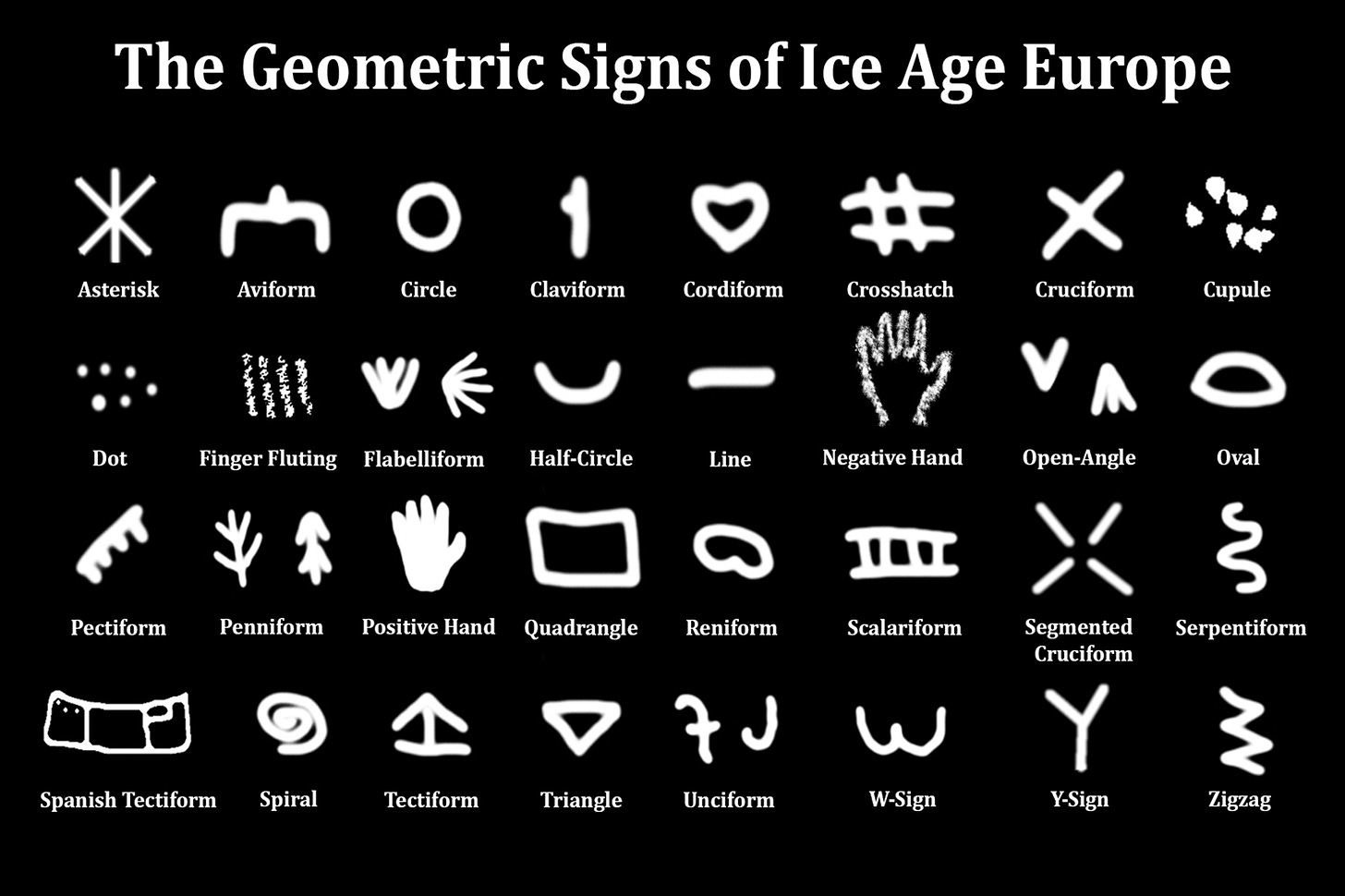

I’m not the first, nor will be the last. Genevieve von Petzinger, a paleoarchaeologist, is more interested in these abstract shapes than she is in the more popular figurative art. She visited almost 370 rock art sites across Europe, documenting as much geometric art as she could. Just 32 signs repeated themselves over and over again.

That really small number tells you that they must have been meaningful to the people who were using them, because they were replicating them.

Genevieve von Petzinger (2017)

I had the fortune to work at Newgrange, Ireland, for a winter season. It is a neolithic megalithic monument (4,500 years old), famous for its rock art. The enormous stones are decorated both inside and out with both indecipherable squiggles and more formal geometric patterns. To go back to the 32 symbols above, the tomb is filled with double spirals, zigzags, dots, cupules, peniforms, quadrangles, ovals and serpentiforms carved into the rock face. The first question all visitors ask, is what do they mean?

Many of the interpretations are linked to Celtic mythology. The problem is that the Celts arrived in Ireland at a much, much later date and wouldn’t have had any more of a clue than we had. At least from a rational, logical perspective.

The textile art in the video below has a (probable) 2000 year old history even though much of what you see here is contemporary. It is created by Shipibo women in Peru. You do not need to watch the whole video, just a few samples, but how many of the above 32 symbols can you find in the textile art below?

The art of the Shipibo has a symmetry that isn’t seen in palaeolithic rock paintings nor neolithic stone art. However, there is considerable overlap in the design forms. I managed to identify aviforms, circles, crosshatching, cordiform, cruciforms, cupules, dots, half-circles, lines, open angles, ovals, quadrangles, serpentiforms, triangles, and zigzags.

How is that these symbols repeat themselves not only across palaeolithic Europe but over thousands of years?

Is it possible these marks are related and have similar significance?

Shipibo art is special, and though we will never know, I’d like to postulate that the manner in which it is generated is possibly how palaeolithic and neolithic art may have been.

The Shipibo are one of the largest ethnic groups in the Peruvian Amazon who have a deep connection with their environment. Their textile (and ceramic) designs represent Ronin Kene (cosmic serpent, anaconda, great mother). However, it isn’t merely a visual representation.

For the Shipibo the skin of Ronin Kene has a radiating, electrifying vibration of light, colour, sound, movement and is the embodiment of all possible patterns and designs past, present, and future. The designs that the Shipibo paint are channels or conduits for this multi-sensorial vibrational fusion of form, light and sound. Although in our cultural paradigm we perceive that the geometric patterns are bound within the border of the textile or ceramic vessel, to the Shipibo the patterns extend far beyond these borders and permeate the entire world.

Howard G. Charing (emphasis my own)

Whereas westerners see colour, patterns and movement, the Shipibo additionally hear and listen to the song of the art. The opposite is also true. An art piece is the manifestation of a song.

As an astonishing demonstration of this I witnessed two Shipiba paint a large ceremonial ceramic pot known as a Mahuetá. The pot was nearly five feet high and had a diameter of about three feet, each of the Shipiba couldn’t see what the other was painting, yet both were whistling the same song, and when they had finished both sides of the complex geometric pattern were identical and matched each side perfectly.

Howard G. Charing

This phenomenon could be attributed to a learned knowledge of the design and considerable practice if it wasn’t for the fact that each is unique.

What is it with humans and trees?

You may have wondered what any of this has to do with trees. This question, what is it with humans and trees was expressed by

in response to the first post in this trees series.Last week’s post on the science of how trees communicate, establishes how other plants and fungi form part of interconnected and symbiotic system that we might begin to think of as an intelligent and ethical complex, one in which we are also a part.

I’m in a redwood forest in Santa Cruz, California, taking dictation for the trees outside my cabin. They speak constantly, even if quietly, communicating above - and underground using sound, scents, signals and vibes. They’re naturally networking, connected with everything that exists, including you.

Including you?

A rich tradition of plant medicine in Shipibo culture is ongoing today. Knowledge is kept alive through maestros, or curanderos, who undergo dietas, a strict regime of social isolation in the forest (which could last up to two years), and dietary restriction with the aim of connecting with and learning from the spirit of a specific master plant. Each dieta may lead not only to personal healing and growth, but also invests the curandero with the song of the master plant with whom they are connected. These songs are known as icaros (ikaros). Icaros drive ritual healing ceremonies, like the ayahuasca ceremonies in which many westerners participate. A curandero may undertake many of these dietas throughout their lives, and it is a measure of their standing as a shaman how many icaros they have been gifted with.

Icaros and art are intricately interwoven and indistinguishable from the other within Shipibo culture. The painted cloth hanging behind this maestra (unfortunately no longer alive) is the visual music for the song she shares.

Shamanic roles complement female artistic ones: a shaman manipulates the visionary design patterns that pervade the universe and that saturate each individual’s spirit.

Gebhart-Sayer (1985)

To western researchers, this parallelism is evident in the structure of both Shipibo songs and visual design.

Shipibo poetic song is a highly structured narrative of repetition and syntactic parallelism. The syntax is plain, but complex figurative expressions (principally the metaphoric use of nouns) abound. Shipibo painting is based on a similar aesthetic principle: a very simple “syntax” of straight and curved lines forms intricate visual patterns.

Levy (date unknown)

The master plants with whom Shipibo curanderos communicate are often psychedelic in nature. To distinguish the ritual use of psychedelic plants from the more western recreational use, they are termed as entheogens.

While we have no means of knowing if palaeolithic and neolithic art stemmed from entheogenic practice, there is good reason to believe that it did. It is highly probable that human engagement with psilocybin predates palaeolithic painters and were used more than a million years ago by homo habilis and homo erectus. There are several reasons for this belief: psilocybin is found in almost all ecozones of the world; the human serotonin receptor system has evolved an enhanced ability to bind with psychedelics; prehistoric art, petroglyphs, and sculptures often closely resemble the observable features of psilocybin mushrooms; and ancient artefacts attest to religious use of psychedelic mushrooms in all of the major regions of the world (Winkelman, M., 2019).

We evolved an ability to listen and communicate with trees through psychedelic use, and even while individuals within western societies enjoy the consumption of magic mushrooms (and other psychedelics), this skill is now restricted to the few surviving societies which have managed to retain a semblance of traditional plant-based ritual. With a resurgence of interest in (and permission to research) the benefits of psychedelics for health and cognitive and behaviour therapy, it may be possible for us to again learn the language of trees.

Under the current dispensation the vast majority of individuals lose, in the course of education, all the openness to inspiration, all the capacity to be aware of other things … which constitutes the conventionally “real” world. . . . Is it too much to hope that a system of education may some day be devised, which shall give results, in terms of human development, commensurate with the time, money, energy and devotion expended? In such a system of education it may be that mescaline or some other chemical substance may play a part by making it possible for young people to taste and see what they have learned about at second hand . . . in the writings of the religious, or the works of poets, painters and musicians.

Aldous Huxley (1953)

Aldous Huxley explored this possibility in his novel, Island, which portrays an ideal culture with a perfect balance of scientific and spiritual thinking, which also incorporated the ritualise use of entheogens for education.

This education is tentatively underway. Shamanic knowledge is remarkably similar to modern geneticist biological knowledge. One scientific study brought molecular biologists to the Amazon to participate in ayahuasca ceremonies as a means for cross-fertilising divergent realms of human knowledge.

You might find the idea of psychedelics making it to the world of education horrifying, and indeed, downright dangerous.

“We [in western culture] have no symbolic vocabulary, no grounded mythological tradition to make our experiences comprehensible to us . . . no senior shamans to help ensure that our [shamanic experience of ] dismemberment be followed by a rebirth”.

Levy (no date)

For us, the experience could be a ‘bad trip’. While entheogens can be regarded as tools to mediate between mind and the world of trees for developmental and healthful purposes, their potential comes from ritual social practice. A ritual context provides entheogen use with the safeguards necessary for furthering our own psychospiritual development (psychologist Howard Gardner referred to this as existential intelligence, a heightened appreciation and attention to cosmological enigmas and exceptional awareness of the metaphysical mysteries). In this regard, most contemporary westerners are at a very infantile stage.

That doesn’t mean trees aren’t talking to us. There are gentler ways to listen than psychedelic use.

In Shinto religion, millions of deities called kami inhabit nature. Trees, as well as other natural entities, including stones, are home to kami. To honour them Shinto temples are situated in the heart of the most extraordinary natural settings. By contrast, Tokyo is one of the most densely populated areas in the world and with it stress-related illness including karōshi and hikikomori, death from overwork and the act of never coming out of your room respectively.

In the 1980s, the term shinrin-yoku was coined, around which an entire government health program was launched. Outside of Japan, it is known as forest bathing and it seems the trees are really trying to help us, if only we’d pay attention.

Up Next

Next week, we’ll journey into the forest to learn about the medical value of spending time around trees and even your indoor plants.

Embers

In September,

began a series Talking Back to Walden. In it she reads and transcribes a passage from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854), a reflection on two years of living simply with nature. Julie provides her own contemplation on the relevance of Thoreau’s reported experience to the contemporary world.I almost missed October’s, subtitled song of the trees. I am glad I didn’t.

I was given a gift of Landlines by Raynor Winn (thank you, Ali!), the story of an epic walk with her dying husband from the north-west of Scotland to Cornwall. I am about half-way through and in love with her observations on nature, the impact of tourism, land ownership and the spirit of walkers on different way paths (not least their incredible courage). Highly recommend.

Beyond The Fiertzeside

The following are the resources consulted to enable the writing of this post. They provide a deeper dive into the topic.

Icaros and Shipibo Art

Communion with the Infinite: The Visual Music of the Shipibo Tribe of the Amazon

and Communion with the Infinite: The Visual Music of the Shipibo Tribe of the Amazon

Beyond Bricolage: Women and Aesthetic Strategies in Latin American Textiles

Palaeolithic Art

Archaic Visions: El Castillo Formative Images from the Upper Palaeolithic

What the mysterious symbols made by early humans can teach us about how we evolved.

Newgrange

Psilocybin (and other psychedelics)

Several scientific articles on psilocybin

Entheogens and Existential Intelligence: The Use of Plant Teachers as Cognitive Tools

The Amazonian Caretakers of Ayahuasca: The Shipibo Tribe

Introduction: Evidence for entheogen use in prehistory and world religions

Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences

Living the Questions: Existential Intelligence in the Context of Holistic Art Education

Prehistoric Art: Paleolithic Origins

Forest Bathing

I will share the resources for forest bathing and its benefits in next week’s post.

And finally …

As I came to the end of this post, I came across an interview with a researcher who proposes that psychedelics were the precursor to religion.

Video: Psychedelics: The Ancient Religion with No Name?

P.S. I’m going out into the garden to hug a tree.

Oh my goodness, Safar, seeing paleolithic cave art in person is a dream of mine! I have been devouring Genevieve von Petzinger's work (both because of my passion for archeology as well as my relationship with the stones as taught to me by an ancestral guide). What a magical experience you must've had in that cave. I truly love your ongoing series about the trees. Thank you for this!

This post just opened up so many rabbit holes for me I can't wait to dive into 🤿 Thanks Safar!