Individuals view art as they read - recursively, contextually, layering experience upon expression until the art is co-created. (Katrina Windon, 2012)1

Even if art is in situ for millennia, like Michael Heizen’s City, its meaning and how it is interpreted will change both with viewer, context and time - continuously co-created. In this sense, all art is ephemeral.

However, as we have seen in prior posts, ephemeral work is intended to decay as part of the natural forces of nature, even after it has passed it into the hands of another. This presents a dilemma for an owner of art or a conservator whose job it is preserve works of art.

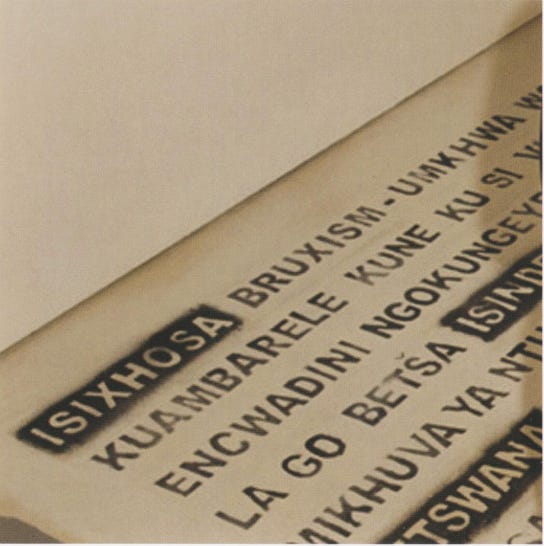

Writing in the Sand by Willem Boshoff was an ephemeral work presented within the confines of the gallery space. He created it within that space, a feat which took three days to complete. It comprises two ‘pages’ of printed words in sand. The words were a homage to the nine officially recognised languages of South Africa. His art is fragile, easily erased, a warning that constitutional recognition isn’t enough to save indigenous languages from extinction. In the work he also wanted to “reverse the dominance and power of privileged tongues”. Some of the included words are abstruse English terms which would confuse even privileged English speakers, terms like bruxism, pognology and cocettism.2 He wrote what he describes as a subversive dictionary, entitled -OLOGIES and -ISMS, his intent being to frustrate the English speaking intelligentia by providing definitions in a lesser known language. The confusion was overcome by, for example, a Zulu speaker coming to the rescue, creating a moment of amusement and a way to break the ice in order to continue the conversation.3

Allyson Purpura assisted Willem in the installation of his work at the National Museum of African Art in South Africa. It was to be displayed for eight months during which time museum staff struggled with its gradual degradation. While welcomed by the artist, the dilemma was felt by those in whose custody it had been given.4 At the heart of the work is loss:

It [Willem’s work] points at an abject extinction of a people’s collective myth when they not longer share it by word of mouth.”5

While ephemeral artists originally rallied against the demands of the market and aimed to democratise art through increasing participation, Mary O’ Neill argues that it should also be understood in terms of its relationship to mourning and loss. Ephemeral art, she says is not just temporary work. It arose out of growing interest in Buddhism during the 1960s when traditional societal structures were being questioned and challenged. The art, has an inherent vice: the use of non-traditional materials lack durability, distinguishing ephemeral art from fixed term temporary art which is destroyed when it is finished. Ephemeral works decay with time, which is a continuous communicative act conveying the work’s meaning. According to this line of reasoning, the use of sand in Willem’s work presented a dilemma for the museum (the inherent vice), but was truly ephemeral in that it was designed to decay throughout the exhibition, the degradation and loss being the communicative act of meaning.6

For those who own or exhibit the work, this raises new ethical questions. From economic, cultural and psychological perspectives art objects are generally viewed as durable. Collectors acquire work because it endures. Ephemeral work is at odds with permanent ownership and the values of those who curate and collect work. This ephemerality can reflect traumatic experiences of bereavement. Knowledge of our mortality pushes us to create permanent structures around us, but ephemeral art doesn’t have structural permanence. Instead it functions not as a reminder of the inevitability of our own death, but that those we love will die. Hence, Mary’s view that many works of ephemeral art create an experience of mourning.7

An explicit example of this is Project for a Memorial by Oscar Muñoz, a Columbian artist who draws attention to vanished persons in politically repressive regimes in South America.8 Using the photographs of people found in the obituary pages of Columbian newspapers, he painted a likeness on hot stones or concrete pavements using only water. As quickly as they were painted, they disappeared.9

The work of artist, Ana Mendieta, serves as another illustrative example. She was born in Cuba and during Castro’s rulership, her father was confined to a political prison. Her family, worried for their future, sent Ana and her sister, then aged 12 and 15 respectively, to the United States. They spent their first few weeks in refugee camps, then in a variety of orphanages and foster homes. Ana became a profuse artist, experimenting with a variety of media, sites and processes, to explore violence against women and cultural alienation. One writer, Kara M. Cabañas, said the best way to understand Ana’s work is in the following poem penned by the artist:10

Much of her work was darkly ritualistic and performative and in 1973, her first time back in Latin America, she undertook her Silueta Series, placing her body in communion with the landscape. In each piece she left an imprint of her body - a silhouette - on the land. The process, she described, is an attempt to reunite with her home. Although tenaciously documented by the artist, when Ana stepped away from her sculpture, the feeling of displacement she experienced can also be felt by the viewer.11

Like Oscar’s vanished persons, Ana’s work elicits mourning for a physical body dislocated in time and place. Perhaps we shouldn’t try to hold on to the ephemeral, but accept the effusion of experience and meaning it offers?

Up Next

I have increasingly learned to go with the flow and to not get uptight about the best laid plans going awry. The more I’ve progressed with The Fiertzeside the more I’ve found it difficult not to pursue a different angle than planned. I am now going to dispense with this ‘what’s next’ section of future posts, unless it is a significant punctuation mark in the flow (like a new series or theme). Next week’s post will still be on this arty theme, but will be a little different and hence a mystery.

Embers

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about how our home is cut off from the garden (the indoor from the outdoor), and the more time I spend inside the house, particularly during the winter months, the more that feeling is exacerbated.

’s most recent post is a reflection on this separation of indoor from outdoor. What struck me in the post was how fear is both socially created and enhanced by this separation. I’ve experienced something similar. Rarely afraid of anything12, the more indoor time I spend, the more anxious I become about venturing into the great unknown, even if that’s camping in the garden. For those who love outdoor nights, I think you’ll especially relate to this:Thank you for reading!

Windon, K. (2012). The Right to Decay with Dignity: Documentation and the Negotiation between an Artist’s Sanction and the Cultural Interest. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 31(2), 142–157. https://doi.org/10.1086/668108

Bruxism means the tendency to grind one’s teeth; pognology is the study of beards; and concettism is the art of appearing intelligent without actually saying much.

Purpura, A. (2009). Framing the Ephemeral. African Arts, 42(3), 11–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627005

Op. cit. Willem Boshoff

O’Neill, M. (2007): Ephemeral Art: Mourning and Loss (a doctoral thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy at Loughborough University).

ibid.

op. cit. Purpura, A. (p. 3)

Cabañas, K. M. (1999). Ana Mendieta: “Pain of Cuba, Body I Am.” Woman’s Art Journal, 20(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1358840

ibid.

I should clarify that statement. I am often afraid. I just don’t let fear get in the way of anything I really want to do. A bit like icy water, if you want to swim in it, you just have to jump in and get wet.

I’m catching up… slowly!

Ephemeral art, to me has always been a gentle way of seeking a higher understanding of understanding and even acceptance, whether that be to place, person or object. It can be taken in its most basic, the Valentines rose for example or in a far more complex and ritualistic fashion as of deeply moving work of Ana Mendieta (I didn’t know this artists Safar - thank you) For which ever reason, the meaning and artistic license either meant (by the artist) or taken (by the viewer) will be remembered differently… or perhaps not at all and this may be even be intended, either way I think all who take the time to see and really understand the reasoning cannot fail to be touched.

"the use of non-traditional materials lack durability" Something like dance.