Imagine transforming this:

into this:

Many city councils are responding to the health benefits of trees in urban settings and in an effort to increase access have intervened to create more available green space in their towns. While this might sound like a positive step it has had an almost contrary result, in fact provoking even greater social injustice.

Urban trees canopies are attractive and therefore more sought after as desirable residential areas for those who work in the city resulting in gentrification, a complaint we first saw in Todmorden after a few women decided to make it edible. So while more people may benefit from the impact of healthy tree pheromones, experiencing reduced stress, lower blood pressure, heatstroke, inflammation, and even increased longevity than they might otherwise have in the same but non-green environment, this is only available to those who can afford it.1 The relationship between health and urban green space can only be understood in the context of the social and political environment where such interventions take place. As an example, in Phoenix, Arizona, a city subjected to high temperatures and extreme heat events, trees provide 25°C surface cooling. However, from 1970, when there was no relationship between income and access to green space, to the year 2000, gentrification has created a clear social division.2

Picture a city with a population of 22 million, situated on a mountain plateau of 2240 metres (7350 feet) above sea level. Its foundation is a lake bed, and because this is also the populations’s water source, the city is sinking at a rate of 25 centimetres (10 inches) annually. Its foundations are sandy and unstable, amplifying earthquakes by 500%. With such a large population, it is a huge waste producer of which 90% is transported by a fleet of 2400 diesel-fuelled refuse trucks to a landfill, creating unhealthy methane emissions.3

This mega metropolis is Mexico City.

Mexico City is no stranger to a very large wealth gap and a history of poverty. The introduction of an increase in the minimum wage did a lot to alleviate the problem. From 2018 to 2022 monetary poverty declined. Income, however, isn’t the only measure of poverty. Multidimensional poverty includes measures of access to essential services such as health care.4 In this respect the situation has been reversed and is partly attributable to gentrification. Middle and low-income communities have been directly or indirectly alienated from the city’s resources.5

While town planners and green space planners are potentially exacerbating inequity, locally generated and group-powered initiatives are transforming both gentrified areas of the city and areas of disadvantage.

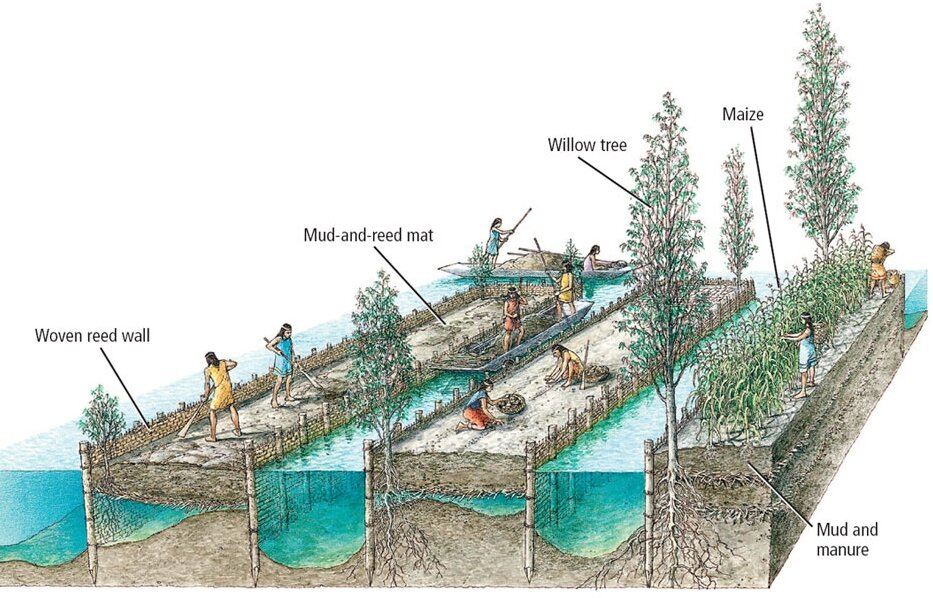

5000 acres of fertile space (see pic below) have enormous potential for feeding a significantly large population with zero waste. Yet only 2.5% of this area is used for this purpose. Instead, it is a bustling tourist attraction, tourism being another factor contributing to social inequity within the city, including access to this beautiful space. Visitors witness narrow canals crammed with colourful trajineras, flat-bottom boats once used for specific celebrations. They now transport the hoards around the historic site of Xochimilco. During the Covid pandemic, the number of visitors was curbed and with supply chains affecting the supply of food, the farmers of these fertile islands began to sell directly to consumers creating a demand which has led to the revival of an agro-ecology practice dating back to 1150 -1350 BCE.6

Formerly known as Tenochtitlán, Mexico City used to be the Aztec capital, and in contrast to its contemporary evolution, no Aztec trash sites have ever been found. Aztec culture included an ingenious method for feeding its population. They developed a traditional agricultural system known as chinampa (Nahuatl: chinãmitl). Small, rectangular plots of fertile arable ground on freshwater swamps and lake wetlands were created to support a wide range of trees, crops and flowers. These would have looked like floating gardens.7

The plots were made from layers of mud, decaying vegetation and other organic matter. Although they had the appearance of floating they were in fact held in place by braiding reeds with stakes fixed into the lake bed and the roots of willow trees. Each was surrounded by a network of canals which enabled easy access and a natural irrigation system.8

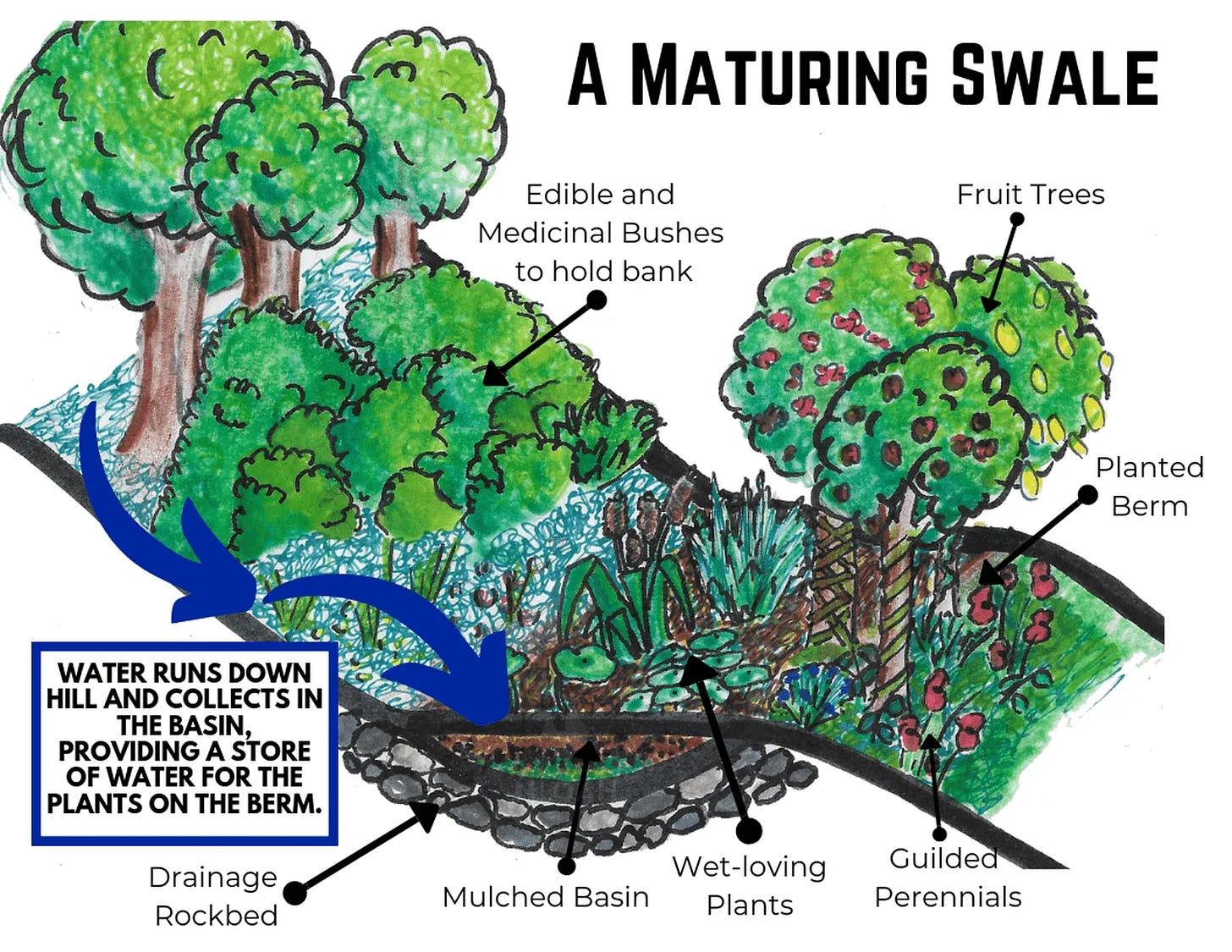

If you’ve joined our gatherings at The Fiertzeside since inception, you may notice how this form of construction is similar to the swale systems incorporated into permaculture design. The difference is that the chinampa system makes use of an existing water source, whereas swales are constructed to capture seasonal rainfall.

The Aztec city of Tenochtitlán supported a population of roughly 300,000 people and was one of the largest centralised populations of its time, yet it produced zero waste. The history of this technique dates back as far as 1150 CE, an innovation of indigenous lake dwellers before it was extensively used by farmers in the Aztec metropolis.9 The system recycled nutrients from waste products as fertiliser of which human excrement was a valuable resource. Urine was also recycled as a fixative in fabric dyes. The city was a thriving economic centre, but didn’t yield the unused waste it does today nor pollute the waters on which the system depended. There was also plenty of room for expansion as this image shows:

Room for expansion, but probably not to 22 million. The Arca Tierra project is now reviving and expanding chinampa practice, while ensuring the health of the water channels between the islands. It provides healthy green space, food, and is increasing biodiversity and the population of threatened species.

What is more interesting is that a thousand year old site is so fertile, that its impact is felt in other parts of the city.

In the current district of Roma Sur, 8000 square metres (two acres) of land has been taken over by local residents. Huerto Roma Verde is located on the site of a high rise residential area which was destroyed by a 1985 earthquake. For 27 years after the event, it became a wasteland of plastic rubbish - a health and environmental concern.10

Paco Ayala, who’d grown up in Roma Sur, ran into a panel beater who explained that he was a social tinsmith, someone who is committed to improving the environment and lives of people in their neighbourhood. He was so inspired by their conversation he too wanted to become a social tinsmith. His orientation was towards environmental protection and green space. Realising that the loss of the little lung of their neighbourhood was imminent, he talked to friends in the community and encouraged them to join him by working, cleaning and designing the space with a view to creating an orchard/garden at its heart.11

They proceeded to create a social, cultural and green space that provides a forum for social, political and economic discussion, food for the community, onsite and external waste recycling, musical events, preventative, natural medicine, and a cool, healing space within the greenhouse that Mexico City has become.

As you can imagine, a landfill on top of earthquake debris is unlikely to be fertile, so the team began by collecting neighbourhood food waste for composting. To speed up the process they had access to a remarkable byproduct of an ancient age. The chinampa soil is so rich that microbial filled organic matter from a chinampa is an aid to decomposition. With it, the project turned the land fill site into a green oasis in a district which has so far resisted gentrification.

The project is self-sustainable, creates its own biogas and even has sufficient clean water to share outside of its own boundaries. It is financed through alliances and hosting its own events and workshops. While a closed system in design it is far from socially isolated.

Paco envisions the centre as part of a wider network. It is itself a local nucleus, but is in dialogue with similar projects around the world, like a spider’s web and it is to this dialogue that will be the focus of our next gathering.

Up Next

In both the food security/sovereignty and tree series we have seen examples of the courageous efforts of quiet revolutionaries, individuals and small groups who make lives better for the people and environment in their neighbourhood. It is easy to think that isolated pockets of action are hardly going to make the huge, urgent change needed in response to the current crisis. While each is a direct response to local conditions and concerns, they are bonded by narrative, one in which civil society can bring about much needed change. Next week, in the last of the tree series posts, we’ll explore more of Paco’s vision and how he views it as part of a movement for global systemic change.

Embers

At The Fiertzeside, we’ve been revamping our living space and winterising our home. It didn’t leave me with a lot of time for reading, but as several of you have just started or intend to host a Substack of your own you may benefit from this Note which

posted this week:Additionally, Joyce Wycoff has written a wonderful series of posts on how to make your Substack resonate with your readers. If your aim is to make a good first impression, here’s a good place to explore several related posts:

There are other highly popular Substack advice sources, but I always cycle back to Joyce’s comprehensive formula: Entice, Enter, Engage, Exit, Extend.

The reason for mentioning Joyce this week isn’t so much for what’s she offers new Substackers, but for the positive news she also shares. In a recent post she challenges the value of trees for carbon sequestration and suggests we should look instead to increasing whale populations:

and I particularly enjoyed this post on looking at the world through wabi-sabi eyes (if you need an uplift, be sure to watch the video about The Restaurant of Mistaken Orders):

Beyond The Fiertzeside

Aside from the references below and sources given above, you might enjoy this 15 minute video on chinampas:

Cole, H. V. S., Lamarca, M. G., Connolly, J. J. T., & Anguelovski, I. (2017). Are green cities healthy and equitable? Unpacking the relationship between health, green space and gentrification. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 71(11), 1118–1121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26383998

Jenertte, G.D., Harlan, S.L., Stefanov, W.L., and Martin, C.A. (2011) Ecosystem services and urban heat risks cape moderation: water, green spaces, and social inequality in Phoenix, USA. Ecological Applications, Vol. 21, No. 7 pp.2637-2651. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41416684?

Leaf of Life (2022) How Mexico City is turning into a farmland Oasis - GREENING THE CITY PROJECT. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MknjOxbXUfU

Georgetown Americas Institute (2023) Experts Dive Deep Into Latest Poverty Trends in Mexico

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, October 31). Gentrification of Mexico City. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:01, November 20, 2023

Borunda, A. (2022) In Mexico City, the pandemic revived Aztec-era island farms. National Geographic

https://www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/chinampas-the-ancient-aztec-floating-gardens-that-hold-promise-for-future-urban-agriculture

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

As always, your posts are always the most heartwarming, hopeful and inspiring to read, which we need more of now than ever. Also, thank you for linking my note in your post. Very kind of you.

@safarfiertze ... what a brilliantly written and illustrated post about a process both ancient and revolutionarily new.

Substack continues to thrill and delight me. Safar's post this morning is one to savor as she shares a well-documented explanation of the Floating Gardens of Xochimilco, not from what I thought was just a tourist-oddity perspective but from the perspective of an agriculture practice that could help save humanity and our planet.

Safar brilliantly uses images to explain this elegant and ancient system and the video she includes of the history and structure of the floating gardens is inspiring and hopeful.

Add to that the surprise of being mentioned and appreciated and my day is just off to a beaming start. I especially appreciate your connection to the Entice-Enter-Engage-Exit-Extend model which I believe can be used by any writer to grow their own Substack

Thanks, Safar, for the amazing gift of your insights and sharing.